This Week - Part 2 of:

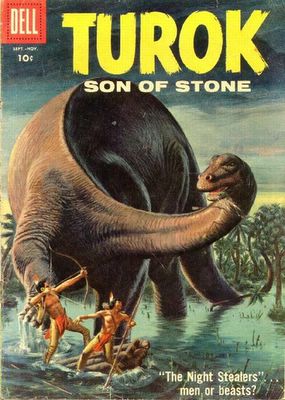

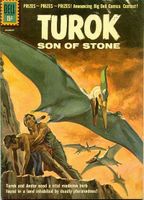

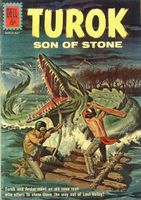

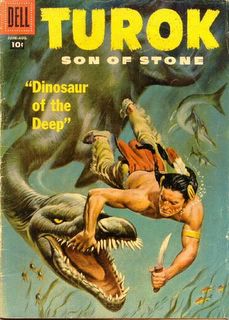

At the time that “Danger in the Nest” appeared in TUROK it was just another storytelling experiment. For a couple of issues, TUROK’s editor had toyed with various approaches to fleshing out each issue with the tried-and-true single-page informative pieces (inside cover sequential pieces “Brontosaurus” and “The Secret of Fire,” the illustrated text piece “Dimetrodon” back cover, all in #7, March-May, 1957; “Duckbill and His Relatives” and “The Tools of Early Man” inside cover pieces in #8). The first ‘back-up’ strip was “Lotor Goes House Hunting” in #7, in which a mother raccoon seeks shelter for her brood (including the titular young raccoon) amid a flood in the ‘lost valley,’ stalked by hungry saurians.

It was a step in the right direction, but still relied on the blatant appeal of a somewhat anachronistic furry warm-blooded mammal protagonist (admittedly a clear step away from human protagonists, but not by much) anthropomorphized by the writer (“’It’s vacant! Come on in!’ Mother Raccoon chirrups happily...”). “Danger in the Nest” eschewed such devices with neat abandon, assuming the reader could and would empathize with a cold-blooded (as it was presumed all prehistoric reptiles were, at that time) protagonist without reliance on Beatrix Potter-like, or Aesopian, conceits.

It was a step in the right direction, but still relied on the blatant appeal of a somewhat anachronistic furry warm-blooded mammal protagonist (admittedly a clear step away from human protagonists, but not by much) anthropomorphized by the writer (“’It’s vacant! Come on in!’ Mother Raccoon chirrups happily...”). “Danger in the Nest” eschewed such devices with neat abandon, assuming the reader could and would empathize with a cold-blooded (as it was presumed all prehistoric reptiles were, at that time) protagonist without reliance on Beatrix Potter-like, or Aesopian, conceits. TUROK’s editor realized they were on to something, as Newman and Maxon were back in the very next issue, working with even greater assurance in the four-pager “The Plight of the Plesiosaur.” A wounded young plesiosaur’s hunting skills are compromised by his injury; he seeks and finds plentiful fresh-water prey inland, until the intrusion of a hungry Tyrannosaurus rex drives him back out to sea. Again, the suspense generated was genuine, the situation and characterizations (Maxon again makes his animals seem nothing more, or less, than living animals, but they are indeed characters) believable throughout, and the short feature was a delight. The slight imposition to the final panel of a moral appropriate to the Eisenhower era (“...some instinct of self-preservation tells the Plesiosaur that the open sea is where he belongs...”) did not compromise the modest accomplishment of the narrative, any more than the completely bogus paleontology did (typically placing species which were separated from one another by millions of years and tens of thousands of miles, being from different geological eras and geographic regions; a failing of almost all dinosaur comics, yesterday and today).

What was important -- and fresh -- was that the conjectured behavior of the dinosaurs and prehistoric creatures was convincing at a ‘gut’ level. Shorn of the need to artificially inflate these incredible animals into the stature of ‘monsters,’ interact with anachronistic human beings, or motivate them to attack contemporary metropolitan areas, Newman and Maxon were free -- for the first time in comics history, or, for that matter, arguably any medium outside of science and pop science texts -- to portray prehistoric animals as animals.

What was important -- and fresh -- was that the conjectured behavior of the dinosaurs and prehistoric creatures was convincing at a ‘gut’ level. Shorn of the need to artificially inflate these incredible animals into the stature of ‘monsters,’ interact with anachronistic human beings, or motivate them to attack contemporary metropolitan areas, Newman and Maxon were free -- for the first time in comics history, or, for that matter, arguably any medium outside of science and pop science texts -- to portray prehistoric animals as animals.  These new kinds of stories relied upon extrapolating possible behaviors for the extinct creatures from that of contemporary life forms: a mother Pteranodon behaving like a protective bird, a hungry plesiosaur seeking easier feeding grounds. Though the writer and cartoonist were hardly paleontologists, they did a credible job with their layman knowledge of zoology and prehistoric life, creating a tactile sense of time, place, and reality that was innovative.

These new kinds of stories relied upon extrapolating possible behaviors for the extinct creatures from that of contemporary life forms: a mother Pteranodon behaving like a protective bird, a hungry plesiosaur seeking easier feeding grounds. Though the writer and cartoonist were hardly paleontologists, they did a credible job with their layman knowledge of zoology and prehistoric life, creating a tactile sense of time, place, and reality that was innovative. These were situations readers young and old could relate to on a primal level no narrative medium had previously tapped: and comics were the ideal medium for such stories.

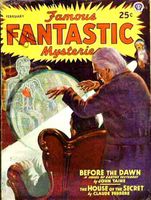

As demonstrated in even the finest ‘paleo’ short stories and novels, from the venerable BEFORE THE DAWN (1934) by mathematician Eric Temple Bell (writing as ‘John Taine’) to paleontologist Robert Bakker’s recent RAPTOR RED (1995), the written word alone does not lend itself to ‘pure’ dinosaur fiction. Those damned latin species names stop a reader’s eye dead, and the repetition of either species names or personalized monikers or ‘nicknames’ become intrusive; further, the contemporary vernacular of even the most careful author wrenches us out of the primordial narrative.

As demonstrated in even the finest ‘paleo’ short stories and novels, from the venerable BEFORE THE DAWN (1934) by mathematician Eric Temple Bell (writing as ‘John Taine’) to paleontologist Robert Bakker’s recent RAPTOR RED (1995), the written word alone does not lend itself to ‘pure’ dinosaur fiction. Those damned latin species names stop a reader’s eye dead, and the repetition of either species names or personalized monikers or ‘nicknames’ become intrusive; further, the contemporary vernacular of even the most careful author wrenches us out of the primordial narrative.  In comics, however, we see the creatures, identify and distinguish them by sight, and know with a glance their diets, strengths, and vulnerabilities. Identifying markings, patterns, or coloration allow both artist and reader to individualize the creatures themselves in a way that is difficult at best via text alone, and the body language of the drawn creatures invites a primal bond between reader and animal almost impossible to evoke with such urgency in literature. Comics, as a medium, is perfectly suited to this ideosyncratic genre, and the appeal of dinosaurs to the traditional comics readership is universal.

In comics, however, we see the creatures, identify and distinguish them by sight, and know with a glance their diets, strengths, and vulnerabilities. Identifying markings, patterns, or coloration allow both artist and reader to individualize the creatures themselves in a way that is difficult at best via text alone, and the body language of the drawn creatures invites a primal bond between reader and animal almost impossible to evoke with such urgency in literature. Comics, as a medium, is perfectly suited to this ideosyncratic genre, and the appeal of dinosaurs to the traditional comics readership is universal. TUROK’s editor was so sure this creative team was on to something that the splash panel of “The Plight of the Plesiosaur” labeled this self-contained parable as the maiden voyage of a new series, entitled "Young Earth." And so began a comics series that appeared in almost every issue of TUROK, SON OF STONE for well over a decade. My collection peters out with TUROK #80 (Sept. 1972), at which point in my collecting days I decided the quality of the comic had dwindled past the point of interest; and there, in its usual spot between chapters of the main TUROK story, sits “Young Earth: Today’s Stone Age Man,” still drawn by Rex Maxon with his characteristic clarity, care, and sense of life (Maxon’s art also graced the latter-day “Gold Key Club Comics” one-pagers dedicated to “Dinosauria,” excerpting art from “Young Earth” narratives to accompany dry text pieces on prehistoric creatures).

“Young Earth” was a revelation: the first true dinosaur comic book series, focusing solely on the prehistoric animals (and, later, on prehistoric man) in compact, concise narratives. Newman’s scripts were marvelously evocative and concise; Maxon’s sketchy, energetic art enlivened the series for the duration of TUROK’s run.

“Young Earth” was a revelation: the first true dinosaur comic book series, focusing solely on the prehistoric animals (and, later, on prehistoric man) in compact, concise narratives. Newman’s scripts were marvelously evocative and concise; Maxon’s sketchy, energetic art enlivened the series for the duration of TUROK’s run. Though the birth of this series, and its impressive longevity, seemed (and remains) inconsequential to those who chart the ebb and flow of comics history and pop culture, it was significant, anticipating all that was to come, including Delgado’s AGE OF REPTILES, my own TYRANT, and the book you now hold in your hands.

So pause a moment, please, and tip your head to Paul S. Newman and Rex Maxon, unsung heroes in comics history, and pioneer creators in our chronology.

'Turok, Son of Stone' is (c) the current copyright holder.

Next Week: Part 6 - "Classics" Illustrated.

Read Part 4 of the series by clicking HERE.

Thanks to the Grand Comic Book Database for the colour covers used in this posting.

Extra thanks to 'Battlin' Bob H. of the KIRBY COMICS BLOG for the last minute Turok scans! Go check out one of my favourite Kirby creations by clicking HERE.

Steve R. Bissette is an artist, writer and film historian who lives in Vermont. He is noted for, amongst many things, his long run as illustrator of SWAMP THING for DC Comics in the 1980's and for self-publishing the acclaimed horror anthology TABOO and a 'real' dinosaur comic TYRANT(R).