Saturday, May 31, 2008

Michael Skrepnick Interview

Brian Switek interviews palaeo-artist Michael Skrepnick at his (Switek's) Laelaps blog.

The Origin of High Growth Rates in Archosaurs

On the origin of high growth rates in archosaurs and their ancient relatives: Complementary histological studies on Triassic archosauriforms and the problem of a “phylogenetic signal” in bone histology. 2008. Armand de Ricqlès, Kevin Padian, Fabien Knoll and John R. Horner. Annales de Paléontologie 94: 57-76.

Abstract [edit]: We sampled the bone histology of various archosauriforms and basal archosaurs from the Triassic and Lower Jurassic: erythrosuchids, proterochampsids, euparkeriids, and basal ornithischian dinosaurs, including forms close to the origin of archosaurs but poorly assessed phylogenetically. The new data suggest that the possibility of reaching and maintaining very high growth rates through ontogeny could have been a basal characteristic of archosauriforms.

This was partly retained (at least during early ontogeny) in most lineages of Triassic pseudosuchians, which nevertheless generally relied on lower growth rates to reach large body sizes. This trend to slower growth seems to have been further emphasized among Crocodylomorpha, which may thus have secondarily reverted toward more generalized reptilian growth strategies. Accordingly, their “typical ectothermic reptilian condition” may be a derived condition within archosauriforms, homoplastic to the generalized physiological condition of basal amniotes. On the other hand, ornithosuchians apparently retained and even enhanced the high growth rates of many basal archosauriforms during most of their ontogenetic trajectories.

The Triassic may have been a time of “experimentation” in growth strategies for several archosauriform lineages, only one of which (ornithodirans) eventually stayed with the higher investment strategy successfully.

Our data again raise the problem of a possible “phylogenetic signal” being carried by bone histology. Bone histology is highly correlated to “functional” characters as size and growth rates which are intensely involved in species-specific “life-history traits”, are under intense scrutiny by selective pressures and may accordingly evolve very rapidly. This rapid evolutionary rate would in turn produce patterns of species-specific variations that could “erase” higher-order taxonomic signals in bone tissue. In other words, this fast turnover would introduce autapomorphies (and homoplasies) at the level of apical (terminal) taxa that could blur the wider “phylogenetic signal”. Thus, the search for generalized apomorphic (or plesiomorphic) conditions of bone histological character-states at supraspecific levels may often be deceptive. Nevertheless, bone tissue phenotypes can reflect a phylogenetic signal at supraspecific levels if homologous elements are used, and if ontogenetic trajectories and size-dependent differences are taken into consideration.

Abstract [edit]: We sampled the bone histology of various archosauriforms and basal archosaurs from the Triassic and Lower Jurassic: erythrosuchids, proterochampsids, euparkeriids, and basal ornithischian dinosaurs, including forms close to the origin of archosaurs but poorly assessed phylogenetically. The new data suggest that the possibility of reaching and maintaining very high growth rates through ontogeny could have been a basal characteristic of archosauriforms.

This was partly retained (at least during early ontogeny) in most lineages of Triassic pseudosuchians, which nevertheless generally relied on lower growth rates to reach large body sizes. This trend to slower growth seems to have been further emphasized among Crocodylomorpha, which may thus have secondarily reverted toward more generalized reptilian growth strategies. Accordingly, their “typical ectothermic reptilian condition” may be a derived condition within archosauriforms, homoplastic to the generalized physiological condition of basal amniotes. On the other hand, ornithosuchians apparently retained and even enhanced the high growth rates of many basal archosauriforms during most of their ontogenetic trajectories.

The Triassic may have been a time of “experimentation” in growth strategies for several archosauriform lineages, only one of which (ornithodirans) eventually stayed with the higher investment strategy successfully.

Our data again raise the problem of a possible “phylogenetic signal” being carried by bone histology. Bone histology is highly correlated to “functional” characters as size and growth rates which are intensely involved in species-specific “life-history traits”, are under intense scrutiny by selective pressures and may accordingly evolve very rapidly. This rapid evolutionary rate would in turn produce patterns of species-specific variations that could “erase” higher-order taxonomic signals in bone tissue. In other words, this fast turnover would introduce autapomorphies (and homoplasies) at the level of apical (terminal) taxa that could blur the wider “phylogenetic signal”. Thus, the search for generalized apomorphic (or plesiomorphic) conditions of bone histological character-states at supraspecific levels may often be deceptive. Nevertheless, bone tissue phenotypes can reflect a phylogenetic signal at supraspecific levels if homologous elements are used, and if ontogenetic trajectories and size-dependent differences are taken into consideration.

Friday, May 30, 2008

The Island Of Thunder

Scott Shaw!’s Oddball Comics brings us another classic to round out our week. From “Star Spangled War Stories #98 (1961) comes “The Island Of Thunder”, written by Robert Kanigher, penciled by Ross Andru and inked by Mike Esposito.

“It’s steel tanks versus 'dinosaur tanks' in another saurian smackdown, courtesy of DC’s 'Star Spangled war Stories!' But this story features a particularly oddball aspect -- it stars a dinosaur-lovin’ paleontologist nicknamed Mr. Bones who finds himself drafted to serve in 'The war that time forgot' – that will have you gushing, 'Tanks for the memories!”

Thursday, May 29, 2008

Placoderm Live Birth

Live birth in the Devonian period. 2008. J. A. Long et al. Nature 453: 650-652.

Abstract: The extinct placoderm fishes were the dominant group of vertebrates throughout the Middle Palaeozoic era, yet controversy about their relationships within the gnathostomes (jawed vertebrates) is partly due to different interpretations of their reproductive biology. Here we document the oldest record of a live-bearing vertebrate in a new ptyctodontid placoderm, Materpiscis attenboroughi gen. et sp. nov., from the Late Devonian Gogo Formation of Australia (approximately 380 million years ago).

The new specimen, remarkably preserved in three dimensions, contains a single, intra-uterine embryo connected by a permineralized umbilical cord. An amorphous crystalline mass near the umbilical cord possibly represents the recrystallized yolk sac. Another ptyctodont from the Gogo Formation, Austroptyctodus gardineri, also shows three small embryos inside it in the same position. Ptyctodontids have already provided the oldest definite evidence for vertebrate copulation, and the new specimens confirm that some placoderms had a remarkably advanced reproductive biology, comparable to that of some modern sharks and rays.

The new discovery points to internal fertilization and viviparity in vertebrates as originating earliest within placoderms.

Museum Victoria has a CGI video of Materpiscis giving birth.

Abstract: The extinct placoderm fishes were the dominant group of vertebrates throughout the Middle Palaeozoic era, yet controversy about their relationships within the gnathostomes (jawed vertebrates) is partly due to different interpretations of their reproductive biology. Here we document the oldest record of a live-bearing vertebrate in a new ptyctodontid placoderm, Materpiscis attenboroughi gen. et sp. nov., from the Late Devonian Gogo Formation of Australia (approximately 380 million years ago).

The new specimen, remarkably preserved in three dimensions, contains a single, intra-uterine embryo connected by a permineralized umbilical cord. An amorphous crystalline mass near the umbilical cord possibly represents the recrystallized yolk sac. Another ptyctodont from the Gogo Formation, Austroptyctodus gardineri, also shows three small embryos inside it in the same position. Ptyctodontids have already provided the oldest definite evidence for vertebrate copulation, and the new specimens confirm that some placoderms had a remarkably advanced reproductive biology, comparable to that of some modern sharks and rays.

The new discovery points to internal fertilization and viviparity in vertebrates as originating earliest within placoderms.

Museum Victoria has a CGI video of Materpiscis giving birth.

Wednesday, May 28, 2008

The Termination of Snowball Earth

Snowball Earth termination by destabilization of equatorial permafrost methane clathrate. 2008. M. Kennedy, et al. Nature 453,: 642-645.

Dolomite cement, formed from oxidized methane as it evolved from melting methane hydrates at the end of the snowball Earth glaciation, present in wave-cut platforms at Marino Rocks, South Australia. The dolomite is orange-red and formed vertical plumbing of tubes and vugs as methane passed upward and disrupted overlying sediment. Credit: M. Kennedy/UC Riverside.

From the press release:

“Our findings document an abrupt and catastrophic means of global warming that abruptly led from a very cold, seemingly stable climate state to a very warm also stable climate state with no pause in between,” said Martin Kennedy.

According to the study, methane clathrate destabilization acted as a runaway feedback to increased warming, and was the tipping point that ended the last snowball Earth. (The snowball Earth hypothesis posits that the Earth was covered from pole to pole in a thick sheet of ice for millions of years at a time.)

Dolomite cement, formed from oxidized methane as it evolved from melting methane hydrates at the end of the snowball Earth glaciation, present in wave-cut platforms at Marino Rocks, South Australia. The dolomite is orange-red and formed vertical plumbing of tubes and vugs as methane passed upward and disrupted overlying sediment. Credit: M. Kennedy/UC Riverside.

An abrupt release of methane about 635 million years ago from ice sheets that then extended to Earth’s low latitudes caused a dramatic shift in climate, triggering a series of events that resulted in global warming and effectively ended the last “snowball” ice age.The researchers posit that the methane was released gradually at first and then in abundance from clathrates – methane ice that forms and stabilizes beneath ice sheets under specific temperatures and pressures. When the ice sheets became unstable, they collapsed, releasing pressure on the clathrates which began to degas.

“Our findings document an abrupt and catastrophic means of global warming that abruptly led from a very cold, seemingly stable climate state to a very warm also stable climate state with no pause in between,” said Martin Kennedy.

According to the study, methane clathrate destabilization acted as a runaway feedback to increased warming, and was the tipping point that ended the last snowball Earth. (The snowball Earth hypothesis posits that the Earth was covered from pole to pole in a thick sheet of ice for millions of years at a time.)

Giant Flying Reptiles Preferred To Walk

A Reappraisal of Azhdarchid Pterosaur Functional Morphology and Paleoecology. 2008. Witton MP and Naish D. PLoS ONE 3(5): e2271.

Life restoration of a group of giant azhdarchids, Quetzalcoatlus northropi, foraging on a Cretaceous fern prairie.

Azhdarchids, named after the Uzbek word for 'dragon', were gigantic toothless pterosaurs. Azhdarchids include the largest of all pterosaurs: some had wingspans exceeding 10 metres and the biggest ones were as tall as a giraffe.

Dr Naish said: “Azhdarchids first became reasonably well known in the 1970s but how they lived has been the subject of much debate. Originally described as vulture-like scavengers, they were later suggested to be mud-probers (sticking their long bills into the ground in search of prey), and later still suggested to make a living by flying over the water’s surface, grabbing fish.

Animals like azhdarchids no longer exist but the closest analogues in the modern world are large ground-feeding birds like ground-hornbills and storks.

“We worked out the range of motion possible in the azhdarchid neck: this bizarrely stiff neck has previously been a problem for other ideas about azhdarchid lifestyle, but it fits with our model as all a terrestrial stalker needs to do its raise and lower its bill tip to the ground.”

Other aspects of azhdarchid anatomy, such as their relatively small padded feet and long but weak jaws often pose problems in other proposed lifestyles but fit perfectly with the terrestrial stalker hypothesis. Mr Witton said: “The small feet of azhdarchids were no good for wading around lake margins or swimming should they land on water but are excellent for strutting around on land. As for what azhdarchids would eat, they’d have snapped up bite-size animals or even bits of fruit. But if your skull is over two metres in length then bite-size includes everything up to a dinosaur the size of a fox.” LINK

Life restoration of a group of giant azhdarchids, Quetzalcoatlus northropi, foraging on a Cretaceous fern prairie.

New research into gigantic flying reptiles has found that they weren’t all gull-like predators grabbing fish from the water but that some were strongly adapted for life on the ground.A new study on one particular type of pterosaur, the azhdarchids, claims they were more likely to stalk animals on foot than to fly. Azhdarchids were probably better than any other ptersosaurs at walking because they had long limbs and skulls well suited for picking up small animals and other food from the ground.

Azhdarchids, named after the Uzbek word for 'dragon', were gigantic toothless pterosaurs. Azhdarchids include the largest of all pterosaurs: some had wingspans exceeding 10 metres and the biggest ones were as tall as a giraffe.

Dr Naish said: “Azhdarchids first became reasonably well known in the 1970s but how they lived has been the subject of much debate. Originally described as vulture-like scavengers, they were later suggested to be mud-probers (sticking their long bills into the ground in search of prey), and later still suggested to make a living by flying over the water’s surface, grabbing fish.

Animals like azhdarchids no longer exist but the closest analogues in the modern world are large ground-feeding birds like ground-hornbills and storks.

“We worked out the range of motion possible in the azhdarchid neck: this bizarrely stiff neck has previously been a problem for other ideas about azhdarchid lifestyle, but it fits with our model as all a terrestrial stalker needs to do its raise and lower its bill tip to the ground.”

Other aspects of azhdarchid anatomy, such as their relatively small padded feet and long but weak jaws often pose problems in other proposed lifestyles but fit perfectly with the terrestrial stalker hypothesis. Mr Witton said: “The small feet of azhdarchids were no good for wading around lake margins or swimming should they land on water but are excellent for strutting around on land. As for what azhdarchids would eat, they’d have snapped up bite-size animals or even bits of fruit. But if your skull is over two metres in length then bite-size includes everything up to a dinosaur the size of a fox.” LINK

Born This Day: Louis Agassiz

May 28, 1807 - Dec. 14, 1873

(Jean) Louis (Rodolphe) Agassiz was a Swiss-born U.S. naturalist, geologist, and teacher who made revolutionary contributions to the study of natural science with landmark work on glacier activity and extinct fishes. Agassiz began his work in Europe, having studied at the University of Munich and then as chair in natural history in Neuchatel in Switzerland. While there he published his landmark multi-volume description and classification of fossil fish.

In 1846 Agassiz came to the U.S. to lecture before Boston's Lowell Institute. Offered a professorship of Zoology and Geology at Harvard in 1848, he decided to stay, becoming a citizen in 1861. His innovative teaching methods altered the character of natural science education in the U.S. Link

More info HERE

Friday, May 23, 2008

Born This Day: Carl Linnaeus

Born May 23, 1707 – Jan. 10, 1778.

From the Linnean Society:

Linnaeus was born in 1707 in Sweden. He headed an expedition to Lapland in 1732, travelling 4,600 miles and crossing the Scandinavian Peninsula by foot to the Arctic Ocean. On the journey he discovered a hundred botanical species. He undertook his medical degree in 1735 in the Netherlands. In 1735, he published Systema Naturae, his classification of plants based on their sexual parts.

species. He undertook his medical degree in 1735 in the Netherlands. In 1735, he published Systema Naturae, his classification of plants based on their sexual parts.

His method of binomial nomenclature using genus and species names was further expounded when he published Fundamenta Botanica (1736) and Classes Plantarum (1738). This system used the flower and the number and arrangements of its sexual organs of stamens and pistils to group plants into twenty-four classes which in turn are divided into orders, genera and species.

In his publications, Linnaeus provided a concise, usable survey of all the world's plants and animals as then known, about 7,700 species of plants and 4,400 species of animals. These works helped to establish and standardize the consistent binomial nomenclature for species which he introduced on a world scale for plants in 1753, and for animals in 1758, and which is used today.

His Systema Naturae 10th edition, volume 1(1758), has accordingly been accepted by international agreement as the official starting point for zoological nomenclature. Scientific names published before then have no validity unless adopted by Linnaeus or by later authors. This confers a high scientific importance on the specimens used by Linnaeus for their preparation, many of which are in his personal collections now treasured by the Linnean Society.

He was granted nobility in 1761, becoming Carl von Linné. He continued his work of classification and as a physician, and remained Rector of the University until 1772.

From the Linnean Society:

Linnaeus was born in 1707 in Sweden. He headed an expedition to Lapland in 1732, travelling 4,600 miles and crossing the Scandinavian Peninsula by foot to the Arctic Ocean. On the journey he discovered a hundred botanical

species. He undertook his medical degree in 1735 in the Netherlands. In 1735, he published Systema Naturae, his classification of plants based on their sexual parts.

species. He undertook his medical degree in 1735 in the Netherlands. In 1735, he published Systema Naturae, his classification of plants based on their sexual parts.His method of binomial nomenclature using genus and species names was further expounded when he published Fundamenta Botanica (1736) and Classes Plantarum (1738). This system used the flower and the number and arrangements of its sexual organs of stamens and pistils to group plants into twenty-four classes which in turn are divided into orders, genera and species.

In his publications, Linnaeus provided a concise, usable survey of all the world's plants and animals as then known, about 7,700 species of plants and 4,400 species of animals. These works helped to establish and standardize the consistent binomial nomenclature for species which he introduced on a world scale for plants in 1753, and for animals in 1758, and which is used today.

His Systema Naturae 10th edition, volume 1(1758), has accordingly been accepted by international agreement as the official starting point for zoological nomenclature. Scientific names published before then have no validity unless adopted by Linnaeus or by later authors. This confers a high scientific importance on the specimens used by Linnaeus for their preparation, many of which are in his personal collections now treasured by the Linnean Society.

He was granted nobility in 1761, becoming Carl von Linné. He continued his work of classification and as a physician, and remained Rector of the University until 1772.

Thursday, May 22, 2008

Pen (with New Attitude)

The May 2008 issue of the Japanese magazine 'Pen' has a 60 page article on dinosaurs. It covers each of the major taxa, recent advances in palaeo-research, localities, museums, artists, scientists, toys, etc. The Japanese love their dinosaurs and love putting together lavish articles like this. The scans below are only a skim through the content.

Born This Day: Sir Arthur Conan Doyle

May 22, 1859 – July 7, 1930

From HERE:

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle was a British writer and creator of Sherlock Holmes. He was born in Edinburgh. His father and uncle were both book illustrators and his mother encouraged his son to explore the world of books. Doyle studied at Edinburgh University and in 1884 he married Louise Hawkins. Doyle qualified as doctor in 1885 and practiced medicine as an eye specialist in Hampshire until 1891 when he became a full time writer. Doyle's first novel about Sherlock Holmes,’ A Study in Scarlet’, was published in 1887.

During the South African war (1899-1902) Doyle served for a few months as senior physician at a field hospital, and wrote ‘The War in South Africa’, in which he defended England's policy. When his son Kingsley died from wounds incurred in World War I, the author dedicated himself in spiritualistic studies.

Doyle's stories of Professor George Edward Challenger in ‘The Lost World’ (1912). The model for the professor was William Rutherford, Doyle's teacher from Edinburgh. Doyle's practice, and other experiences, expeditions as ship's surgeon to the Arctic and West Coast of Africa, service in the Boer War, defenses of George Edalji and Oscar Slater, two men wrongly imprisoned, provided much material for his writings.

The Lost World:

From HERE:

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle was a British writer and creator of Sherlock Holmes. He was born in Edinburgh. His father and uncle were both book illustrators and his mother encouraged his son to explore the world of books. Doyle studied at Edinburgh University and in 1884 he married Louise Hawkins. Doyle qualified as doctor in 1885 and practiced medicine as an eye specialist in Hampshire until 1891 when he became a full time writer. Doyle's first novel about Sherlock Holmes,’ A Study in Scarlet’, was published in 1887.

During the South African war (1899-1902) Doyle served for a few months as senior physician at a field hospital, and wrote ‘The War in South Africa’, in which he defended England's policy. When his son Kingsley died from wounds incurred in World War I, the author dedicated himself in spiritualistic studies.

Doyle's stories of Professor George Edward Challenger in ‘The Lost World’ (1912). The model for the professor was William Rutherford, Doyle's teacher from Edinburgh. Doyle's practice, and other experiences, expeditions as ship's surgeon to the Arctic and West Coast of Africa, service in the Boer War, defenses of George Edalji and Oscar Slater, two men wrongly imprisoned, provided much material for his writings.

The Lost World:

Born This Day: Oliver Perry Hay

May 22, 1846 – Novemeber 2, 1930

Hay was an American paleontologist whose catalogs of fossil vertebrates greatly organized existing knowledge and became standard references. Hay's primary scientific interest was the study of the Pleistocene vertebrata of North America and he is renowned for his work on skull and brain anatomy. His first major work was his Bibliography and Catalogue of the Fossil Vertebrata of North America (1902), supplemented by two more volumes (1929-30). Hay also wrote on the evidence of early humans in North America. link

Hay was an American paleontologist whose catalogs of fossil vertebrates greatly organized existing knowledge and became standard references. Hay's primary scientific interest was the study of the Pleistocene vertebrata of North America and he is renowned for his work on skull and brain anatomy. His first major work was his Bibliography and Catalogue of the Fossil Vertebrata of North America (1902), supplemented by two more volumes (1929-30). Hay also wrote on the evidence of early humans in North America. link

Wednesday, May 21, 2008

Gerobatrachus: The Missing Link Between Frogs & Salamanders

A stem batrachian from the Early Permian of Texas and the origin of frogs and salamanders. 2008. Jason S. Anderson et al., Nature 453: 515-518.

An Early Permian landscape, with Gerobatrachus hottoni lunging at the mayfly Protoreisma between stands of Calamites and under a fallen Walchia conifer. Art by Michael SkrepnickFrom the press release:

The examination and detailed description of the fossil, Gerobatrachus hottoni (meaning Hotton’s elder frog), proves the previously disputed fact that some modern amphibians, frogs and salamanders evolved from one ancient amphibian group called temnospondyls.

“The dispute arose because of a lack of transitional forms. This fossil seals the gap,” says Jason Anderson, assistant professor, University of Calgary Faculty of Veterinary Medicine and lead scientist in the study.

The Gerobatrachus fossil provides a much fuller understanding of the origin and evolution of modern amphibians. The skull, backbone and teeth of Gerobatrachus have a mixture of frog and salamander features—the fossil has two fused bones in the ankle, which is normally only seen in salamanders, and a very large tympanic ear (ear drum). It also has a lightly built and wide skull similar to that of a frog. Its backbone is exactly intermediate in number between the modern frogs and salamanders and more primitive amphibians.

The new fossil also addresses a controversy over molecular clock estimates, or the general time salamanders and frogs evolved into two distinct groups.

“With this new data our best estimate indicates that frogs and salamanders separated from each other sometime between 240 and 275 million years ago, much more recently than previous molecular data had suggested,” says Robert Reisz.

Gerobatrachus was originally discovered in Texas in 1995 by a field party from the Smithsonian Institution that included the late Nicholas Hotton, for whom the fossil is named. It remained unstudied until it was “rediscovered” by Anderson’s team. It took countless hours of work on the small, extremely delicate fossil to remove the overlying layers of rock and uncover the bones to reveal the anatomy of the spectacular looking skeleton.

“It is bittersweet to learn about frog origins in this Year of the Frog, dedicated to informing the public about the current global amphibian decline,” continues Anderson. “Hopefully we won’t ever learn about their extinction.”

The description of an ancient amphibian that millions of years ago swam in quiet pools and caught mayflies on the surrounding land in Texas has set to rest one of the greatest current controversies in vertebrate evolution.

An Early Permian landscape, with Gerobatrachus hottoni lunging at the mayfly Protoreisma between stands of Calamites and under a fallen Walchia conifer. Art by Michael Skrepnick

The examination and detailed description of the fossil, Gerobatrachus hottoni (meaning Hotton’s elder frog), proves the previously disputed fact that some modern amphibians, frogs and salamanders evolved from one ancient amphibian group called temnospondyls.

“The dispute arose because of a lack of transitional forms. This fossil seals the gap,” says Jason Anderson, assistant professor, University of Calgary Faculty of Veterinary Medicine and lead scientist in the study.

The Gerobatrachus fossil provides a much fuller understanding of the origin and evolution of modern amphibians. The skull, backbone and teeth of Gerobatrachus have a mixture of frog and salamander features—the fossil has two fused bones in the ankle, which is normally only seen in salamanders, and a very large tympanic ear (ear drum). It also has a lightly built and wide skull similar to that of a frog. Its backbone is exactly intermediate in number between the modern frogs and salamanders and more primitive amphibians.

The new fossil also addresses a controversy over molecular clock estimates, or the general time salamanders and frogs evolved into two distinct groups.

“With this new data our best estimate indicates that frogs and salamanders separated from each other sometime between 240 and 275 million years ago, much more recently than previous molecular data had suggested,” says Robert Reisz.

Gerobatrachus was originally discovered in Texas in 1995 by a field party from the Smithsonian Institution that included the late Nicholas Hotton, for whom the fossil is named. It remained unstudied until it was “rediscovered” by Anderson’s team. It took countless hours of work on the small, extremely delicate fossil to remove the overlying layers of rock and uncover the bones to reveal the anatomy of the spectacular looking skeleton.

“It is bittersweet to learn about frog origins in this Year of the Frog, dedicated to informing the public about the current global amphibian decline,” continues Anderson. “Hopefully we won’t ever learn about their extinction.”

First Dinosaur Trackway From Yemen

First Dinosaur Tracks from the Arabian Peninsula. 2008. A. S. Schulp et al., PLoS ONE 3(5): e2243.

A Yemeni journalist spotted one of the trackways in 2003, about 50 kilometers north of the capital of Sana’a in the village of Madar. Only a few dinosaur fossils have been reported so far from the Arabian Peninsula, including isolated bones from the Sultanate of Oman, which Schulp has studied, and possible fragments of a long-necked dinosaur from Yemen.

In late 2006, the research team conducted further field work at the Madar site. By taking measurements on the shape and angle of the different digits, they were able to identify the bipedal dinosaur as an ornithopod. The size, shape and spacing of the quadrupedal prints were used to identify the body size, travel speed and other distinguishing features of the animals in the sauropod herd, Stevens said.

The rocks in which the dinosaur tracks are preserved are likely Late Jurassic in age, some 150 million years old, according to Al-Wosabi. The tracks probably went unnoticed for so long, Schulp explained, because they were too big to be spotted by the untrained eye and were partially covered by rubble and debris. “It isn’t a surprise that they were overlooked,” he said.

The Yemen Geological Survey has implemented protective measures to preserve the trackways and to improve their accessibility to tourists, the researchers report.

Scientists report evidence of a large ornithopod dinosaur, as well as a herd of 11 small and large sauropods walking along a Mesozoic coastal mudflat in what is now the Republic of Yemen.From the press release:

A Yemeni journalist spotted one of the trackways in 2003, about 50 kilometers north of the capital of Sana’a in the village of Madar. Only a few dinosaur fossils have been reported so far from the Arabian Peninsula, including isolated bones from the Sultanate of Oman, which Schulp has studied, and possible fragments of a long-necked dinosaur from Yemen.

In late 2006, the research team conducted further field work at the Madar site. By taking measurements on the shape and angle of the different digits, they were able to identify the bipedal dinosaur as an ornithopod. The size, shape and spacing of the quadrupedal prints were used to identify the body size, travel speed and other distinguishing features of the animals in the sauropod herd, Stevens said.

The rocks in which the dinosaur tracks are preserved are likely Late Jurassic in age, some 150 million years old, according to Al-Wosabi. The tracks probably went unnoticed for so long, Schulp explained, because they were too big to be spotted by the untrained eye and were partially covered by rubble and debris. “It isn’t a surprise that they were overlooked,” he said.

The Yemen Geological Survey has implemented protective measures to preserve the trackways and to improve their accessibility to tourists, the researchers report.

Macroevolutionary Changes In Snakes

Adaptive Evolution and Functional Redesign of Core Metabolic Proteins in Snakes. 2008. T.A. Castoe et al., PLoS ONE 3(5): e2201.

From the press release:

Researchers now have evidence that major macroevolutionary changes in snakes (e.g., physiological and metabolic adaptations and venom evolution) have been accompanied by massive functional redesign of core metabolic proteins.

“The molecular evolutionary results are remarkable, and set a new precedence for extreme protein evolutionary adaptive redesign. This represents the most dramatic burst of protein evolution in an otherwise highly conserved protein that I know of,” said Dr. David Pollock.

Over the last ten years, scientists have shown that snakes have remarkable abilities to regulate heart and digestive system development. They endure among the most extreme shifts in aerobic metabolism known in vertebrates. This has made snakes an excellent model for studying organ development, as well as physiological and metabolic regulation. The reasons that snakes are so unique had not previously been identified at the molecular level. In this recent study by Pollock and colleagues, the researchers show that mitochondrially-encoded oxidative phosphorylation proteins in snakes have endured a remarkable process of evolutionary redesign that may explain why snakes have such unique metabolism and physiology.

From the press release:

Researchers now have evidence that major macroevolutionary changes in snakes (e.g., physiological and metabolic adaptations and venom evolution) have been accompanied by massive functional redesign of core metabolic proteins.

“The molecular evolutionary results are remarkable, and set a new precedence for extreme protein evolutionary adaptive redesign. This represents the most dramatic burst of protein evolution in an otherwise highly conserved protein that I know of,” said Dr. David Pollock.

Over the last ten years, scientists have shown that snakes have remarkable abilities to regulate heart and digestive system development. They endure among the most extreme shifts in aerobic metabolism known in vertebrates. This has made snakes an excellent model for studying organ development, as well as physiological and metabolic regulation. The reasons that snakes are so unique had not previously been identified at the molecular level. In this recent study by Pollock and colleagues, the researchers show that mitochondrially-encoded oxidative phosphorylation proteins in snakes have endured a remarkable process of evolutionary redesign that may explain why snakes have such unique metabolism and physiology.

Born This Day: Mary Anning

May 21, 1799 - March 9, 1847

From Today in Science History:

Mary was an English fossil collector who made her first significant discovery at the age of 11 or 12 (sources differ on the details), when she found a complete skeleton of an Ichthyosaurus, from the Jurassic period. The ten-meter (30 feet) long skeleton created a sensation and made her famous.

when she found a complete skeleton of an Ichthyosaurus, from the Jurassic period. The ten-meter (30 feet) long skeleton created a sensation and made her famous.

Anning's determination and keen scientific interest in fossils derived from her father's interest in fossil hunting, and a need for the income derived from them to support her family after his death. in 1810. She sold large fossils to noted paleontologists of the day, and smaller ones to the tourist trade. In 1823, Anning made another great discovery, found the first complete Plesiosaurus.

Later in her life, the Geological Society of London granted Anning an honorary membership.

Listen to an MP3 clip of the Mary Anning song by the Articokes HERE.

From Today in Science History:

Mary was an English fossil collector who made her first significant discovery at the age of 11 or 12 (sources differ on the details),

when she found a complete skeleton of an Ichthyosaurus, from the Jurassic period. The ten-meter (30 feet) long skeleton created a sensation and made her famous.

when she found a complete skeleton of an Ichthyosaurus, from the Jurassic period. The ten-meter (30 feet) long skeleton created a sensation and made her famous. Anning's determination and keen scientific interest in fossils derived from her father's interest in fossil hunting, and a need for the income derived from them to support her family after his death. in 1810. She sold large fossils to noted paleontologists of the day, and smaller ones to the tourist trade. In 1823, Anning made another great discovery, found the first complete Plesiosaurus.

Later in her life, the Geological Society of London granted Anning an honorary membership.

Listen to an MP3 clip of the Mary Anning song by the Articokes HERE.

Monday, May 19, 2008

Genes From Extinct Tasmanian Tiger Resurrected

Resurrection of DNA Function In Vivo from an Extinct Genome. 2008. A. J. Pask, et al. PLoS ONE 3(5): e2240.

Researchers have extracted genes from the extinct Tasmanian tiger (thylacine), inserted it into a mouse and observed a biological function – this is a world first for the use of the DNA of an extinct species to induce a functional response in another living organism.

The results showed that the thylacine Col2a1 gene has a similar function in developing cartilage and bone development as the Col2a1 gene does in the mouse.

“Up until now we have only been able to examine gene sequences from extinct animals. This research was developed to go one step further to examine extinct gene function in a whole organism,” he said. The last known Tasmanian tiger died in captivity in the Hobart Zoo in 1936. This enigmatic marsupial carnivore was hunted to extinction in the wild in the early 1900s.

Researchers say fortunately some thylacine pouch young and adult tissues were preserved in alcohol in several museum collections around the world. The research team isolated DNA from 100 year old ethanol fixed specimens. After authenticating this DNA as truly thylacine, it was inserted into mouse embryos and its function examined. The thylacine DNA was resurrected, showing a function in the developing mouse cartilage, which will later form the bone.

The thylacine, Thylacinus cynocephalus. (a) Young male thylacine in Hobart Zoo in 1928, photograph (Q4437). (b) One of the preserved pouch young specimens (head length 34 mm) from which DNA was extracted, from the Museum Victoria collection. (c-f) The skull of the thylacine (c,e) compared with that of the domestic dog Canis canis (d,f). Scale bar = 5cm.From the press release:

Researchers have extracted genes from the extinct Tasmanian tiger (thylacine), inserted it into a mouse and observed a biological function – this is a world first for the use of the DNA of an extinct species to induce a functional response in another living organism.

The results showed that the thylacine Col2a1 gene has a similar function in developing cartilage and bone development as the Col2a1 gene does in the mouse.

“Up until now we have only been able to examine gene sequences from extinct animals. This research was developed to go one step further to examine extinct gene function in a whole organism,” he said. The last known Tasmanian tiger died in captivity in the Hobart Zoo in 1936. This enigmatic marsupial carnivore was hunted to extinction in the wild in the early 1900s.

Researchers say fortunately some thylacine pouch young and adult tissues were preserved in alcohol in several museum collections around the world. The research team isolated DNA from 100 year old ethanol fixed specimens. After authenticating this DNA as truly thylacine, it was inserted into mouse embryos and its function examined. The thylacine DNA was resurrected, showing a function in the developing mouse cartilage, which will later form the bone.

Born This Day: Carl E. Akeley

May 19, 1864 - Nov 17, 1926

This is not quite palaeo, but anyone’s who’s been to the AMNH has marveled at the wonderful dioramas and mounts in the Hall of African Mammals. That hall exists thanks to the efforts of Carl Akeley who was the kind of advendurer that Indy Jones could only dream of being. He died on an African expedition in 1926, ten years before this hall was completed and was buried in a place depicted in the Hall's famous Gorilla Diorama. Of course we approach collecting and conservation differently today, but Akeley is to be commended for his love of nature and his desire to present its hidden corners to the world. I wonder if Carl Denham was named after him?

That hall exists thanks to the efforts of Carl Akeley who was the kind of advendurer that Indy Jones could only dream of being. He died on an African expedition in 1926, ten years before this hall was completed and was buried in a place depicted in the Hall's famous Gorilla Diorama. Of course we approach collecting and conservation differently today, but Akeley is to be commended for his love of nature and his desire to present its hidden corners to the world. I wonder if Carl Denham was named after him?

From Today In Science History:

Carl Ethan Akeley was an American naturalist and explorer who developed the taxidermic method for mounting museum displays to show animals in their natural surroundings. His method of applying skin on a finely molded replica of the body of the animal gave results of unprecedented realism and elevated taxidermy from a craft to an art. He mounted the skeleton of the famous African elephant Jumbo. He invented the Akeley cement gun to use while mounting animals, and the Akeley camera which was used to capture the first movies of gorillas.

From the AMNH, “The American Museum of Natural History’s “Akeley Hall of African Mammals” is considered by many to be among the world's greatest museum displays. The Hall is also a monument to Carl Akeley, the innovator who created it. Akeley was a dedicated explorer, taxidermist, sculptor, and photographer who led teams of scientists and artists on several expeditions to Africa during the first two decades of this century. There, he and his colleagues carefully studied, catalogued, and collected the plants and animals that even then were disappearing. He brought many specimens of that world back to the Museum, where he created this hall, with its twenty-eight dioramas.”

This also let’s me plug this wonderful book, “Windows on Nature: The Great Habitat Dioramas of the American Museum of Natural History”. There are also lots of mostly out of print books about Akeley and his work – well worth the effort to find some of them.

This is not quite palaeo, but anyone’s who’s been to the AMNH has marveled at the wonderful dioramas and mounts in the Hall of African Mammals.

That hall exists thanks to the efforts of Carl Akeley who was the kind of advendurer that Indy Jones could only dream of being. He died on an African expedition in 1926, ten years before this hall was completed and was buried in a place depicted in the Hall's famous Gorilla Diorama. Of course we approach collecting and conservation differently today, but Akeley is to be commended for his love of nature and his desire to present its hidden corners to the world. I wonder if Carl Denham was named after him?

That hall exists thanks to the efforts of Carl Akeley who was the kind of advendurer that Indy Jones could only dream of being. He died on an African expedition in 1926, ten years before this hall was completed and was buried in a place depicted in the Hall's famous Gorilla Diorama. Of course we approach collecting and conservation differently today, but Akeley is to be commended for his love of nature and his desire to present its hidden corners to the world. I wonder if Carl Denham was named after him?From Today In Science History:

Carl Ethan Akeley was an American naturalist and explorer who developed the taxidermic method for mounting museum displays to show animals in their natural surroundings. His method of applying skin on a finely molded replica of the body of the animal gave results of unprecedented realism and elevated taxidermy from a craft to an art. He mounted the skeleton of the famous African elephant Jumbo. He invented the Akeley cement gun to use while mounting animals, and the Akeley camera which was used to capture the first movies of gorillas.

From the AMNH, “The American Museum of Natural History’s “Akeley Hall of African Mammals” is considered by many to be among the world's greatest museum displays. The Hall is also a monument to Carl Akeley, the innovator who created it. Akeley was a dedicated explorer, taxidermist, sculptor, and photographer who led teams of scientists and artists on several expeditions to Africa during the first two decades of this century. There, he and his colleagues carefully studied, catalogued, and collected the plants and animals that even then were disappearing. He brought many specimens of that world back to the Museum, where he created this hall, with its twenty-eight dioramas.”

This also let’s me plug this wonderful book, “Windows on Nature: The Great Habitat Dioramas of the American Museum of Natural History”. There are also lots of mostly out of print books about Akeley and his work – well worth the effort to find some of them.

Sunday, May 18, 2008

World's Biggest 'Baby' Dinosaur Tracks Found in Korea

From Digital Chosunilbo:

The world’s largest fossil of a playground of baby dinosaurs going back over 100 million years has been found in Korea. The Natural Heritage Center under the National Research Institute of Cultural Heritage announced Thursday that it found the fossil trackway of two baby sauropods dating back to 110 million years in Euiseong County, North Gyeongsang Province.

There are a total of 61 footprints stretching over 4.25 meters, making them the largest fossil trackway of baby dinosaurs in the world.

The world’s largest fossil of a playground of baby dinosaurs going back over 100 million years has been found in Korea. The Natural Heritage Center under the National Research Institute of Cultural Heritage announced Thursday that it found the fossil trackway of two baby sauropods dating back to 110 million years in Euiseong County, North Gyeongsang Province.

There are a total of 61 footprints stretching over 4.25 meters, making them the largest fossil trackway of baby dinosaurs in the world.

Saturday, May 17, 2008

Stephen Jay Gould's Library Donated To Stanford

From the press release:

During his career, Gould assembled what he believed was a definitive library of the history of early paleontology, said Rhonda Shearer, Gould's widow. Now, the collection of books, papers and artifacts that helped inform his writing and teaching is, for the most part, in the Stanford University Libraries, with the balance expected to arrive soon. It is an immense amount of material.

helped inform his writing and teaching is, for the most part, in the Stanford University Libraries, with the balance expected to arrive soon. It is an immense amount of material.

Gould owned approximately 1,500 rare, antiquarian books, some dating back to the late 1400s. His library of more contemporary books numbers roughly 8,000 volumes. Although the total number of papers has yet to be determined, the librarians working on the collection estimate they will stretch more than 500 linear feet—a good deal longer than a football field.

"It's a great acquisition," said University Librarian Michael Keller. "Steve Gould was a tremendous popularizer of science, and he was, more importantly, a deep scientist. He had a big, broad mind, working on lots of different interesting problems."

Perhaps even more surprising than the books he collected is what he did with them.

"He actually used them, and he annotated on many of them in pencil, in the margins," Trujillo said. "He didn't really treat them as artifacts, he treated them as a working research library, and it is clear that is what he did, even though they're really quite amazing rare books."

Keller said the plan is to digitize Gould's articles, as well as the sources from which he drew both inspiration and information, and cross-link the source materials to the endnotes and citations in his writing. The goal will be to make all of Gould's papers freely available over the Internet to anyone who wants to see them, whether schoolchildren or scholars.

Recreating the twists and turns that lead to Gould's different writings should be an interesting process, as the nature of his collection of artifacts suggests. Anyone who found inspiration in items as disparate as a small piece of wood riddled with termite holes or the eye lenses of a flying fish (still stuffed into a small black tube with a tissue stuffed in the open end) probably had an interesting way of looking at things.

During his career, Gould assembled what he believed was a definitive library of the history of early paleontology, said Rhonda Shearer, Gould's widow. Now, the collection of books, papers and artifacts that

helped inform his writing and teaching is, for the most part, in the Stanford University Libraries, with the balance expected to arrive soon. It is an immense amount of material.

helped inform his writing and teaching is, for the most part, in the Stanford University Libraries, with the balance expected to arrive soon. It is an immense amount of material.Gould owned approximately 1,500 rare, antiquarian books, some dating back to the late 1400s. His library of more contemporary books numbers roughly 8,000 volumes. Although the total number of papers has yet to be determined, the librarians working on the collection estimate they will stretch more than 500 linear feet—a good deal longer than a football field.

"It's a great acquisition," said University Librarian Michael Keller. "Steve Gould was a tremendous popularizer of science, and he was, more importantly, a deep scientist. He had a big, broad mind, working on lots of different interesting problems."

Perhaps even more surprising than the books he collected is what he did with them.

"He actually used them, and he annotated on many of them in pencil, in the margins," Trujillo said. "He didn't really treat them as artifacts, he treated them as a working research library, and it is clear that is what he did, even though they're really quite amazing rare books."

Keller said the plan is to digitize Gould's articles, as well as the sources from which he drew both inspiration and information, and cross-link the source materials to the endnotes and citations in his writing. The goal will be to make all of Gould's papers freely available over the Internet to anyone who wants to see them, whether schoolchildren or scholars.

Recreating the twists and turns that lead to Gould's different writings should be an interesting process, as the nature of his collection of artifacts suggests. Anyone who found inspiration in items as disparate as a small piece of wood riddled with termite holes or the eye lenses of a flying fish (still stuffed into a small black tube with a tissue stuffed in the open end) probably had an interesting way of looking at things.

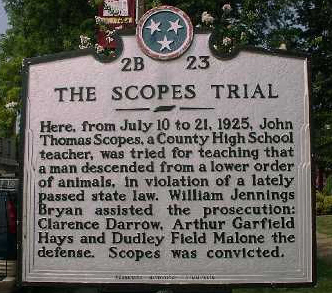

This Day In History: Scopes Monkey Trial Law Repealed

From Today In Science History:

On this day in 1967, the governor of Tennessee signed into law the repeal of the 1925 state law prohibiting the teaching of evolution. The original law had made it "unlawful for any teacher in any of the Universities, Normals and all other public schools of the State which are supported in whole or in part by the public school funds of the State, to teach any theory that denies the story of the Divine Creation of man as taught in the Bible, and to teach instead that man has descended from a lower order of animals." It was this law that was tested in what became known as the "Scopes monkey trial." Scopes was found guilty, but acquitted on a technicality upon appeal. The law itself remained a Tennessee state statute for 42 years.

Born This Day: Thomas Davidson

May 17, 1817 – Oct. 14, 1885

Davison was a Scottish naturalist and paleontologist who became known as an authority on brachiopods. His major work, Monograph of British Fossil Brachiopoda, was published by the Palaeontographical Society. Together with supplements, this comprised six quarto volumes with more than 200 plates drawn on stone by the author. Upon his death, he bequeathed his fine collection of recent and fossil brachiopoda to the British Museum.

Davison was a Scottish naturalist and paleontologist who became known as an authority on brachiopods. His major work, Monograph of British Fossil Brachiopoda, was published by the Palaeontographical Society. Together with supplements, this comprised six quarto volumes with more than 200 plates drawn on stone by the author. Upon his death, he bequeathed his fine collection of recent and fossil brachiopoda to the British Museum.

Friday, May 16, 2008

Danger and Adventure!

I’m still on the road and, frankly, it has been a slow news week. So, why don’t we visit Scott Shaw!’s Oddball Comics site for a behind the scenes look at this issue of Danger and Adventure from 1955.

Wednesday, May 14, 2008

Today In History: Darwin Starts "The Origin of The Species"

Today In Science History tells us that in 1856, Charles Darwin began writing his book, The Origin of Species, sitting in the study of his country home in Down, England.

So all you graduate students surfing the web -- back to work!

Tuesday, May 13, 2008

Preservation of Ancient Biomolecules

The latest issue of Comptes Rendus Palevol has a number of articles on ancient biomolecules and their preservation:

Environment and excavation: Pre-lab impacts on ancient DNA analyses. 2008. Ruth Bollongino et al. Comptes Rendus PalevolAbstract: Ancient DNA (aDNA) analyses enjoy an increasing role in palaeontological, archaeological and archaeozoological research. The limiting factor for aDNA studies is the degree of DNA preservation. Our study on 291 prehistoric cattle remains from Europe, the Near East and North Africa revealed that DNA preservation is mainly influenced by geographic and climatic conditions. Especially in hot climates, the preservation of sample material is generally low. We observed that these specimens are prone to further degradation and contamination during and after excavation. We give a description of the main caveats and a short guideline for adequate sample handling in order to facilitate the cooperation between archaeologists and geneticists and to improve the outcome of future research.

Comparing rates of recrystallisation and the potential for preservation of biomolecules from the distribution of trace elements in fossil bones. 2008. Clive N. Trueman, et al. Comptes Rendus PalevolAbstract: Preservation of intact macromolecules and geochemical signals in fossil bones is mainly controlled by the extent of post-mortem interaction between bones and sediment pore waters. Trace elements such as lanthanum are added to bone post-mortem from pore waters, and where uptake occurs via a simple process of diffusion and adsorption, the elemental distribution can be used to assess the relative extent of bone-pore water interaction and rate of recrystallisation. Distribution profiles can be parameterised effectively using simple exponential equations, and the extent of bone–water interaction compared within and between sites. In this study, the distribution of lanthanum within bone was determined by laser ablation ICP–MS in 60 archaeological and fossil bones from Pleistocene and Cretaceous sites. The rates of recrystallisation and potential for preservation of intact biogeochemical signals vary significantly within and between sites. Elemental profiles within fossil bones hold promise as a screening technique to prospect for intact biomolecules and as a taphonomic tool.

Microscopic, chemical and molecular methods for examining fossil preservation. 2008. Mary Higby Schweitzer et al. Comptes Rendus PalevolAbstract: Advances in technology over the past two decades have resulted in unprecedented access to data from biological specimens. These data have expanded our understanding of physical characteristics, physiological, cellular and subcellular processes, and evolutionary relationships at the molecular level and beyond. Paleontological and archaeological sciences have recently begun to apply these technologies to fossil and subfossil representatives of extinct organisms. Data derived from multidisciplinary, non-traditional techniques can be difficult to decipher, and without a basic understanding of the type of information provided by these methods, their usefulness for fossil studies may be overlooked. This review describes some of these powerful new analytical tools, the data that may be accessible through their use, advantages and limitations, and how they can be applied to fossil material to elucidate characteristics of extinct organisms and their paleoecological environments.

Sunday, May 11, 2008

Big Mammals Evolve & Die Out Faster

Higher origination and extinction rates in larger mammals. 2008. L.H. Liow et al. PNAS 105: 6097-6102.

Abstract: Do large mammals evolve faster than small mammals or vice versa?

Because the answer to this question contributes to our understanding of how life-history affects long-term and large-scale evolutionary patterns, and how microevolutionary rates scale-up to macroevolutionary rates, it has received much attention. A satisfactory or consistent answer to this question is lacking, however.

Here, we take a fresh look at this problem using a large fossil dataset of mammals from the Neogene of the Old World (NOW). Controlling for sampling biases, calculating per capita origination and extinction rates of boundary-crossers and estimating survival probabilities using capture-mark-recapture (CMR) methods, we found the recurring pattern that large mammal genera and species have higher origination and extinction rates, and therefore shorter durations.

This pattern is surprising in the light of molecular studies, which show that smaller animals, with their shorter generation times and higher metabolic rates, have greater absolute rates of evolution.

However, higher molecular rates do not necessarily translate to higher taxon rates because both the biotic and physical environments interact with phenotypic variation, in part fueled by mutations, to affect origination and extinction rates.

To explain the observed pattern, we propose that the ability to evolve and maintain behavior such as hibernation, torpor and burrowing, collectively termed "sleep-or-hide" (SLOH) behavior, serves as a means of environmental buffering during expected and unexpected environmental change. SLOH behavior is more common in some small mammals, and, as a result, SLOH small mammals contribute to higher average survivorship and lower origination probabilities among small mammals.

Abstract: Do large mammals evolve faster than small mammals or vice versa?

Because the answer to this question contributes to our understanding of how life-history affects long-term and large-scale evolutionary patterns, and how microevolutionary rates scale-up to macroevolutionary rates, it has received much attention. A satisfactory or consistent answer to this question is lacking, however.

Here, we take a fresh look at this problem using a large fossil dataset of mammals from the Neogene of the Old World (NOW). Controlling for sampling biases, calculating per capita origination and extinction rates of boundary-crossers and estimating survival probabilities using capture-mark-recapture (CMR) methods, we found the recurring pattern that large mammal genera and species have higher origination and extinction rates, and therefore shorter durations.

This pattern is surprising in the light of molecular studies, which show that smaller animals, with their shorter generation times and higher metabolic rates, have greater absolute rates of evolution.

However, higher molecular rates do not necessarily translate to higher taxon rates because both the biotic and physical environments interact with phenotypic variation, in part fueled by mutations, to affect origination and extinction rates.

To explain the observed pattern, we propose that the ability to evolve and maintain behavior such as hibernation, torpor and burrowing, collectively termed "sleep-or-hide" (SLOH) behavior, serves as a means of environmental buffering during expected and unexpected environmental change. SLOH behavior is more common in some small mammals, and, as a result, SLOH small mammals contribute to higher average survivorship and lower origination probabilities among small mammals.