“In a letter of complaint sent in 2007 to New Mexico government officials, Martz, Mathew Wedel of the University of California at Merced and Michael Taylor of the University of Portsmouth, UK, wrote: “It is our strong suspicion the [New Mexico Museum team members] deliberately abused their editorial powers to take credit for observations and insights of Parker and Martz.” Such actions, the letter argues, corrupt the scientific process and harm young researchers. Because Lucas largely edits the Bulletin, he and his team have been able “to mass produce essentially self-published and non-peer-reviewed papers”, the letter claims.

Lucas is known in the palaeontology community for his desire to publish a high volume of papers. He acknowledges that his “tough” approach has brought him into conflict with researchers before. “They are obviously angry,” he says, but the complaint “doesn't have any substance”.

The New Mexico cultural-affairs department, which oversees the museum, conducted a review of two of the instances last October and concluded that the allegations were groundless. But some experts call that review a whitewash, claiming that it failed to follow accepted practices of US academic institutions faced with claims of misconduct. Now all three cases are before the Ethics Education Committee of the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology, a professional organization based in Northbrook, Illinois, which is awaiting responses from the New Mexico team before making a ruling.”

Thursday, January 31, 2008

Fossil Row

Rex Dalton, in the latest issue of Nature, has an article about complaints levels at some members of the New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science.

Blue-Eyed Humans Have a Single, Common Ancestor

Blue eye color in humans may be caused by a perfectly associated founder mutation in a regulatory element located within the HERC2 gene inhibiting OCA2 expression. 2008. H. Eiberg et al. Human Genetics. Published online: 3 January 2008

From the press release:

New research shows that people with blue eyes have a single, common ancestor. A team at the University of Copenhagen have tracked down a genetic mutation which took place 6-10,000 years ago and is the cause of the eye colour of all blue-eyed humans alive on the planet today.

“Originally, we all had brown eyes”, said Professor Eiberg from the Department of Cellular and Molecular Medicine. “But a genetic mutation affecting the OCA2 gene in our chromosomes resulted in the creation of a “switch”, which literally “turned off” the ability to produce brown eyes”. The OCA2 gene codes for the so-called P protein, which is involved in the production of melanin, the pigment that gives colour to our hair, eyes and skin.

The “switch”, which is located in the gene adjacent to OCA2 does not, however, turn off the gene entirely, but rather limits its action to reducing the production of melanin in the iris – effectively “diluting” brown eyes to blue. The switch’s effect on OCA2 is very specific therefore. If the OCA2 gene had been completely destroyed or turned off, human beings would be without melanin in their hair, eyes or skin colour – a condition known as albinism.

Variation in the colour of the eyes from brown to green can all be explained by the amount of melanin in the iris, but blue-eyed individuals only have a small degree of variation in the amount of melanin in their eyes. “From this we can conclude that all blue-eyed individuals are linked to the same ancestor,” says Professor Eiberg. “They have all inherited the same switch at exactly the same spot in their DNA.” Brown-eyed individuals, by contrast, have considerable individual variation in the area of their DNA that controls melanin production.

Read the article HERE.

From the press release:

New research shows that people with blue eyes have a single, common ancestor. A team at the University of Copenhagen have tracked down a genetic mutation which took place 6-10,000 years ago and is the cause of the eye colour of all blue-eyed humans alive on the planet today.

“Originally, we all had brown eyes”, said Professor Eiberg from the Department of Cellular and Molecular Medicine. “But a genetic mutation affecting the OCA2 gene in our chromosomes resulted in the creation of a “switch”, which literally “turned off” the ability to produce brown eyes”. The OCA2 gene codes for the so-called P protein, which is involved in the production of melanin, the pigment that gives colour to our hair, eyes and skin.

The “switch”, which is located in the gene adjacent to OCA2 does not, however, turn off the gene entirely, but rather limits its action to reducing the production of melanin in the iris – effectively “diluting” brown eyes to blue. The switch’s effect on OCA2 is very specific therefore. If the OCA2 gene had been completely destroyed or turned off, human beings would be without melanin in their hair, eyes or skin colour – a condition known as albinism.

Variation in the colour of the eyes from brown to green can all be explained by the amount of melanin in the iris, but blue-eyed individuals only have a small degree of variation in the amount of melanin in their eyes. “From this we can conclude that all blue-eyed individuals are linked to the same ancestor,” says Professor Eiberg. “They have all inherited the same switch at exactly the same spot in their DNA.” Brown-eyed individuals, by contrast, have considerable individual variation in the area of their DNA that controls melanin production.

Read the article HERE.

Wednesday, January 30, 2008

Published Today (1868): Darwin’s ‘Variation’

From Today In Science History:

In 1868, Charles Darwin's book - Variation of Animals and Plants under Domestication - was published. He was 58. It is probably the second in importance of all his works. This was a follow-up work, written in response to criticisms that his theory of evolution was unsubstantiated. Darwin here supports his views via analysis of various aspects of plant and animal life, including an inventory of varieties and their physical and behavioral characteristics, and an investigation of the impact of a species' surrounding environment and the effect of both natural and forced changes in this environment.

- Variation of Animals and Plants under Domestication - was published. He was 58. It is probably the second in importance of all his works. This was a follow-up work, written in response to criticisms that his theory of evolution was unsubstantiated. Darwin here supports his views via analysis of various aspects of plant and animal life, including an inventory of varieties and their physical and behavioral characteristics, and an investigation of the impact of a species' surrounding environment and the effect of both natural and forced changes in this environment.

In 1868, Charles Darwin's book

- Variation of Animals and Plants under Domestication - was published. He was 58. It is probably the second in importance of all his works. This was a follow-up work, written in response to criticisms that his theory of evolution was unsubstantiated. Darwin here supports his views via analysis of various aspects of plant and animal life, including an inventory of varieties and their physical and behavioral characteristics, and an investigation of the impact of a species' surrounding environment and the effect of both natural and forced changes in this environment.

- Variation of Animals and Plants under Domestication - was published. He was 58. It is probably the second in importance of all his works. This was a follow-up work, written in response to criticisms that his theory of evolution was unsubstantiated. Darwin here supports his views via analysis of various aspects of plant and animal life, including an inventory of varieties and their physical and behavioral characteristics, and an investigation of the impact of a species' surrounding environment and the effect of both natural and forced changes in this environment.

Tuesday, January 29, 2008

The Evolution of Colour Change in Chameleons

Selection for social signalling drives the evolution of chameleon colour change. 2008. D. Stuart-Fox & A. Moussalli, PLoS Biol 6(1): e25. Open Access Article

From the press release:

Chameleons can use color change to camouflage and to signal to other chameleons, but new research hows that the need to rapidly signal to other chameleons, and not the need to camouflage from predators, has driven the evolution of this characteristic trait.

The research shows that the dramatic color changes of chameleons are tailored to aggressively display to conspecific competitors and to seduce potential mates. Because these signals are quick—chameleons can change color in a matter of milliseconds—the animal can afford to make it obvious, as the risk that a predator will notice is limited. This finding means that the evolution of color change serves to make chameleons more noticeable, the complete opposite of the camouflage hypothesis. The amount of color change possible varies between species, and the authors cleverly capitalise on this in their experiments.

Stuart-Fox and Moussalli measured color change by setting up chameleon “duels”: sitting two males on a branch opposite each other and measuring the color variation. By comparing species that can change color dramatically to those that only change slightly, and considering the evolutionary interrelationships of the species, the researchers showed that dramatic color change is consistently associated with the use of color change as a social signal to other chameleons. The degree of change is not predicted by the amount of color variation in the chameleons’ habitat, as would be expected if chameleons had evolved such remarkable color changing abilities in order to camouflage.

Readers of this blog will know that evolution based on sexual selection for ornamentation or possible colour patterns for some dinosaurs has been suggested many times.

From the press release:

Chameleons can use color change to camouflage and to signal to other chameleons, but new research hows that the need to rapidly signal to other chameleons, and not the need to camouflage from predators, has driven the evolution of this characteristic trait.

The research shows that the dramatic color changes of chameleons are tailored to aggressively display to conspecific competitors and to seduce potential mates. Because these signals are quick—chameleons can change color in a matter of milliseconds—the animal can afford to make it obvious, as the risk that a predator will notice is limited. This finding means that the evolution of color change serves to make chameleons more noticeable, the complete opposite of the camouflage hypothesis. The amount of color change possible varies between species, and the authors cleverly capitalise on this in their experiments.

Stuart-Fox and Moussalli measured color change by setting up chameleon “duels”: sitting two males on a branch opposite each other and measuring the color variation. By comparing species that can change color dramatically to those that only change slightly, and considering the evolutionary interrelationships of the species, the researchers showed that dramatic color change is consistently associated with the use of color change as a social signal to other chameleons. The degree of change is not predicted by the amount of color variation in the chameleons’ habitat, as would be expected if chameleons had evolved such remarkable color changing abilities in order to camouflage.

Readers of this blog will know that evolution based on sexual selection for ornamentation or possible colour patterns for some dinosaurs has been suggested many times.

Jenny Clack Wins NAS Award

Jennifer A. Clack, ScD, FLS, Professor and Curator of Vertebrate Palaeontology, and  Acting Director of the University Museum of Zoology, Cambridge is the 2008 recipient of the Daniel Giraud Elliot Medal from the National Academt of Sciences “for studies of the first terrestrial vertebrates and the water-to-land transition, as illuminated in her book Gaining Ground”.

Acting Director of the University Museum of Zoology, Cambridge is the 2008 recipient of the Daniel Giraud Elliot Medal from the National Academt of Sciences “for studies of the first terrestrial vertebrates and the water-to-land transition, as illuminated in her book Gaining Ground”.

The award is for meritorious work in zoology or paleontology published in a three- to five-year period and was established through the Daniel Giraud Elliot Fund by gift of Miss Margaret Henderson Elliot.

From Kevin Padian’s post to the Vertpaleo List:

Acting Director of the University Museum of Zoology, Cambridge is the 2008 recipient of the Daniel Giraud Elliot Medal from the National Academt of Sciences “for studies of the first terrestrial vertebrates and the water-to-land transition, as illuminated in her book Gaining Ground”.

Acting Director of the University Museum of Zoology, Cambridge is the 2008 recipient of the Daniel Giraud Elliot Medal from the National Academt of Sciences “for studies of the first terrestrial vertebrates and the water-to-land transition, as illuminated in her book Gaining Ground”.The award is for meritorious work in zoology or paleontology published in a three- to five-year period and was established through the Daniel Giraud Elliot Fund by gift of Miss Margaret Henderson Elliot.

From Kevin Padian’s post to the Vertpaleo List:

“Jenny is the first vertebrate paleontologist (or, in her case, palaeontologist) since Al Romer in 1956 to have been awarded the medal, only the second female to have been awarded it (the other being Libby Hyman in 1951), and the first British awardee since D'Arcy Thompson”.

Monday, January 28, 2008

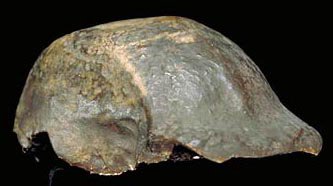

Born Today: Eugene Dubois

Jan. 28, 1858-Dec. 16, 1940

Eugene Dubois joined the Dutch Army as a medical officer, and used spare time from his medical duties to search for fossils, first in Sumatra and then in Java. He searched on the banks of the Solo River, with two assigned engineers and a crew of convict labourers to help him. In September 1890, his workers found a human, or human-like, fossil at Koedoeng Broeboes. This consisted of the right side of the chin of a lower jaw and three attached teeth. In August 1891 he found a primate molar tooth.

He searched on the banks of the Solo River, with two assigned engineers and a crew of convict labourers to help him. In September 1890, his workers found a human, or human-like, fossil at Koedoeng Broeboes. This consisted of the right side of the chin of a lower jaw and three attached teeth. In August 1891 he found a primate molar tooth.

Two months later and one meter away was found an intact skullcap, the fossil which would be known as Java Man. In August 1892, a third primate fossil, an almost complete left thigh bone, was found between 10 and 15 meters away from the skullcap.

meter away was found an intact skullcap, the fossil which would be known as Java Man. In August 1892, a third primate fossil, an almost complete left thigh bone, was found between 10 and 15 meters away from the skullcap.

In 1894 Dubois published a description of his fossils, naming them Pithecanthropus erectus (now Home erectus), describing it as neither ape nor human, but something intermediate. In 1895 he returned to Europe to promote the fossil and his interpretation. A few scientists enthusiastically endorsed Dubois' work, but most disagreed with his interpretation. Many scientists pointed out similarities between the Java Man skullcap and Neandertal fossils.

Around 1900 Dubois ceased to discuss Java Man, and hid the fossils in his home while he moved on to other research topics. geology and paleontology. It was not until 1923 that Dubois, under pressure from scientists, once again allowed access to the Java Man fossils. That and the discovery of similar fossils caused it to once again become a topic of debate.

Skull cap (Trinil 2, holotype of Home erectus) from HERE.

Eugene Dubois joined the Dutch Army as a medical officer, and used spare time from his medical duties to search for fossils, first in Sumatra and then in Java.

He searched on the banks of the Solo River, with two assigned engineers and a crew of convict labourers to help him. In September 1890, his workers found a human, or human-like, fossil at Koedoeng Broeboes. This consisted of the right side of the chin of a lower jaw and three attached teeth. In August 1891 he found a primate molar tooth.

He searched on the banks of the Solo River, with two assigned engineers and a crew of convict labourers to help him. In September 1890, his workers found a human, or human-like, fossil at Koedoeng Broeboes. This consisted of the right side of the chin of a lower jaw and three attached teeth. In August 1891 he found a primate molar tooth.Two months later and one

meter away was found an intact skullcap, the fossil which would be known as Java Man. In August 1892, a third primate fossil, an almost complete left thigh bone, was found between 10 and 15 meters away from the skullcap.

meter away was found an intact skullcap, the fossil which would be known as Java Man. In August 1892, a third primate fossil, an almost complete left thigh bone, was found between 10 and 15 meters away from the skullcap.In 1894 Dubois published a description of his fossils, naming them Pithecanthropus erectus (now Home erectus), describing it as neither ape nor human, but something intermediate. In 1895 he returned to Europe to promote the fossil and his interpretation. A few scientists enthusiastically endorsed Dubois' work, but most disagreed with his interpretation. Many scientists pointed out similarities between the Java Man skullcap and Neandertal fossils.

Around 1900 Dubois ceased to discuss Java Man, and hid the fossils in his home while he moved on to other research topics. geology and paleontology. It was not until 1923 that Dubois, under pressure from scientists, once again allowed access to the Java Man fossils. That and the discovery of similar fossils caused it to once again become a topic of debate.

Skull cap (Trinil 2, holotype of Home erectus) from HERE.

Saturday, January 26, 2008

Mark Schultz : Modern Master

Mark would never refer to himself that way but it IS the title of the latest volume (#15) in the TwoMorrows "Modern Masters" book series showcasing different artists. It features an informative interview covering Mark's diverse art and writing career, and has lots of art not seen elsewhere. You can pick it up HERE

Born This Day: Roy Chapman Andrews

Jan. 26, 1884 – March 11, 1960.

Photo from Charles Knight’s article, “Parade of Life Through The Ages”, National Geographic, Feb. 1942.

From the American Museum of Natural History web site:

Adventurer, administrator, and Museum promoter — Andrews spent his entire career at the American Museum of Natural History, where he rose through the ranks from departmental assistant, to expedition organizer, to Museum director. He became world famous as leader of the Central Asiatic Expeditions, a series of expeditions to Mongolia that collected, among other things, dinosaur eggs. But on these expeditions, Andrews himself found few fossils, and during his career he was not known as an influential scientist. Instead, Andrews filled the role of promoter, creating immense excitement and successfully advancing the research and exhibition goals of the museum.

Learn about the Roy Chapman Andrews Society HERE.

Photo from Charles Knight’s article, “Parade of Life Through The Ages”, National Geographic, Feb. 1942.

From the American Museum of Natural History web site:

Adventurer, administrator, and Museum promoter — Andrews spent his entire career at the American Museum of Natural History, where he rose through the ranks from departmental assistant, to expedition organizer, to Museum director. He became world famous as leader of the Central Asiatic Expeditions, a series of expeditions to Mongolia that collected, among other things, dinosaur eggs. But on these expeditions, Andrews himself found few fossils, and during his career he was not known as an influential scientist. Instead, Andrews filled the role of promoter, creating immense excitement and successfully advancing the research and exhibition goals of the museum.

Learn about the Roy Chapman Andrews Society HERE.

Friday, January 25, 2008

Fossils On The Block Again

From Physorg.com:

A Triceratops skeleton from a private European collection, is the highlight of the April 16 Christie's auction in Paris. It will mark the first time that such a dinosaur specimen goes up for public sale since a T-Rex called "Sue" was sold in New York in October 1997.

In all, 150 items from natural history collections - fossils, skeletons and minerals - valued at some 1.6 million euros will be up for auction. A sabre-toothed tiger cranium is expected to fetch up to 45,000 euros, while the fossilized giant shark teeth have been valued at up to 4,000 euros.

Christie's said it hoped to build on the success of last year's paleontology auction that brought in more than one million euros and established 12 world records. Also up for bids will be a Tyrannosaurus egg (?!) mineralized in agate, valued at between 20,000 and 25,000 euros; and an Apatosaurus dinosaur tibia from the Jurassic Period, which is expected to raise up to 30,000 euros.

A private German museum is offering a well-conserved cranium of an Edmontosaurus, a duck-beaked dinosaur, estimated at between 70,000 and 80,000 euros.

A Triceratops skeleton from a private European collection, is the highlight of the April 16 Christie's auction in Paris. It will mark the first time that such a dinosaur specimen goes up for public sale since a T-Rex called "Sue" was sold in New York in October 1997.

In all, 150 items from natural history collections - fossils, skeletons and minerals - valued at some 1.6 million euros will be up for auction. A sabre-toothed tiger cranium is expected to fetch up to 45,000 euros, while the fossilized giant shark teeth have been valued at up to 4,000 euros.

Christie's said it hoped to build on the success of last year's paleontology auction that brought in more than one million euros and established 12 world records. Also up for bids will be a Tyrannosaurus egg (?!) mineralized in agate, valued at between 20,000 and 25,000 euros; and an Apatosaurus dinosaur tibia from the Jurassic Period, which is expected to raise up to 30,000 euros.

A private German museum is offering a well-conserved cranium of an Edmontosaurus, a duck-beaked dinosaur, estimated at between 70,000 and 80,000 euros.

DRI DinoTour 2008

En route to the Albertosaurus bone bed in Dry Island Provincial Park

Once again the Dinosaur Research Institute is running their Dinotour July 4 to7, 2008.Dinotour is a unique opportunity to discover Alberta's palaeontological treasures with world renowned scientists Dr. Philip Currie and Dr. Eva Koppelhus of the University of Alberta and Darren Tanke, Royal Tyrrell Museum of Paleontology.

Highlights of this 4 day family-orientated tour:

- Unique opportunity to learn about the dinosaurs of Alberta

- Explore a dinosaur quarry with Philip, Eva and Darren in the Albertosaurus bonebed in Dry Island Buffalo Jump Provincial Park north east of Calgary

- Tour the Royal Tyrrell Museum in Drumheller

- Hike and explore in the Drumheller area and at Dinosaur Provincial Park near Brooks

Tour includes:

- Guided tour including deluxe bus transportation to and from Calgary

- Three nights accommodation (double occupancy) and all meals

- Admission to the Royal Tyrrell Museum and the Dinosaur Provincial Park Field Station

- Guidebook, T-shirt and goodie bag

- Charitable tax receipt for a portion of the fees

This program supports the work of the Dinosaur Research Institute, a non-profit charitable organization that finances dinosaur research.

To register or for more information contact: Corliss.Moore @ inglewoodgrove.com

Welcome To The Anthropocene

Are we now living in the Anthropocene? 2008. Jan Zalasiewicz et al., GSA Today 18.

From the press release:

Geologists from the University of Leicester propose that humankind has so altered the Earth that it has brought about an end to one epoch of Earth’s history and marked the start of a new epoch - the Anthropocene.

They have identified human impact through phenomena such as:

• Transformed patterns of sediment erosion and deposition worldwide

• Major disturbances to the carbon cycle and global temperature

• Wholesale changes to the world’s plants and animals

• Ocean acidification

The scientists analysed a proposal made by Nobel Prize-winning chemist Paul Crutzen in 2002. He suggested the Earth had left the Holocene and started the Anthropocene era because of the global environmental effects of increased human population and economic development.

The researchers argue that the dominance of humans has so physically changed Earth that there is increasingly less justification for linking pre- and post-industrialized Earth within the same epoch - the Holocene.

The scientists said their findings present the scholarly groundwork for consideration by the International Commission on Stratigraphy for formal adoption of the Anthropocene as the youngest epoch of, and most recent addition to, the Earth's geological timescale.

They state: “Sufficient evidence has emerged of stratigraphically significant change (both elapsed and imminent) for recognition of the Anthropocene—currently a vivid yet informal metaphor of global environmental change—as a new geological epoch to be considered for formalization by international discussion.”

This is an open access article and the PDF should be HERE

From the press release:

Geologists from the University of Leicester propose that humankind has so altered the Earth that it has brought about an end to one epoch of Earth’s history and marked the start of a new epoch - the Anthropocene.

They have identified human impact through phenomena such as:

• Transformed patterns of sediment erosion and deposition worldwide

• Major disturbances to the carbon cycle and global temperature

• Wholesale changes to the world’s plants and animals

• Ocean acidification

The scientists analysed a proposal made by Nobel Prize-winning chemist Paul Crutzen in 2002. He suggested the Earth had left the Holocene and started the Anthropocene era because of the global environmental effects of increased human population and economic development.

The researchers argue that the dominance of humans has so physically changed Earth that there is increasingly less justification for linking pre- and post-industrialized Earth within the same epoch - the Holocene.

The scientists said their findings present the scholarly groundwork for consideration by the International Commission on Stratigraphy for formal adoption of the Anthropocene as the youngest epoch of, and most recent addition to, the Earth's geological timescale.

They state: “Sufficient evidence has emerged of stratigraphically significant change (both elapsed and imminent) for recognition of the Anthropocene—currently a vivid yet informal metaphor of global environmental change—as a new geological epoch to be considered for formalization by international discussion.”

This is an open access article and the PDF should be HERE

World's Oldest Horseshoe Crabs

The oldest horseshoe crab: a new xiphosurid from Late Ordovician konservat- lagerstätten deposits, Manitoba, Canada. 2008. D. M. Rudkin et al. Palaeontology 51: 1–9.

From the Winnipeg Sun and the home of Neil Young:

The 445 million year old horseshoe crab fossils found near Churchill and in the Grand Rapids Uplands area, are now the oldest of their kind on record, said Graham Young, curator of Geology and Palaeontology at the Manitoba Museum.

"It's great we can find things in Manitoba that are new to Manitoba but also new to the world," he said. The fossilized creatures, which exist in a slightly more evolved state today, have a head shaped like a horseshoe, earning them their name. Modern horseshoe crabs can be up to two feet long, said Young. Although they've evolved, they share characteristics with their early ancestors.

This marks the first time horseshoe crab fossils have been discovered in Manitoba, said Young, adding they date back 100 million years earlier than the previously oldest known ones.

From the Winnipeg Sun and the home of Neil Young:

The 445 million year old horseshoe crab fossils found near Churchill and in the Grand Rapids Uplands area, are now the oldest of their kind on record, said Graham Young, curator of Geology and Palaeontology at the Manitoba Museum.

"It's great we can find things in Manitoba that are new to Manitoba but also new to the world," he said. The fossilized creatures, which exist in a slightly more evolved state today, have a head shaped like a horseshoe, earning them their name. Modern horseshoe crabs can be up to two feet long, said Young. Although they've evolved, they share characteristics with their early ancestors.

This marks the first time horseshoe crab fossils have been discovered in Manitoba, said Young, adding they date back 100 million years earlier than the previously oldest known ones.

Thursday, January 24, 2008

Chicxulub Landed In Deep Water

Importance of pre-impact crustal structure for the asymmetry of the Chicxulub impact crater. S. P. S. Gulick et al., Nature Geosciences, Published online: 13 January 2008.

From the press release:

An increase in the atmospheric concentration of sulfate aerosols caused by the impact would have made it deadlier in two ways: by altering climate (sulfate aerosols in the upper atmosphere can have a cooling effect) and by generating acid rain (water vapor can help to flush the lower atmosphere of sulfate aerosols, causing acid rain). Earlier studies had suggested both effects might result from the impact, but to a lesser degree.

An increase in acid rain might help explain why reef and surface dwelling ocean creatures were affected along with large vertebrates on land and in the sea. As it fell on the water, acid rain could have turned the oceans more acidic. There is some evidence that marine organisms more resistant to a range of pH survived while those more sensitive did not.

Gulick says the mass extinction event was probably not caused by just one mechanism, but rather a combination of environmental changes acting on different time scales, in different locations. For example, many large land animals might have been baked to death within hours or days of the impact as ejected material fell from the sky, heating the atmosphere and setting off firestorms. More gradual changes in climate and acidity might have had a larger impact in the oceans.

From the press release:

The most detailed three-dimensional seismic images yet of the Chicxulub crater, a mostly submerged and buried impact crater on the Mexico coast, may modify a theory explaining the extinction of 70 percent of life on Earth 65 million years ago.

Image:NASA

The Chicxulub crater was formed when an asteroid struck on the coast of the Yucatan Peninsula. Most scientists agree the impact played a major role in the "KT Extinction Event" that caused the extinction of most life on Earth, including the dinosaurs. New research shows that the asteroid landed in deeper water than previously assumed and therefore released about 6.5 times more water vapor into the atmosphere.An increase in the atmospheric concentration of sulfate aerosols caused by the impact would have made it deadlier in two ways: by altering climate (sulfate aerosols in the upper atmosphere can have a cooling effect) and by generating acid rain (water vapor can help to flush the lower atmosphere of sulfate aerosols, causing acid rain). Earlier studies had suggested both effects might result from the impact, but to a lesser degree.

An increase in acid rain might help explain why reef and surface dwelling ocean creatures were affected along with large vertebrates on land and in the sea. As it fell on the water, acid rain could have turned the oceans more acidic. There is some evidence that marine organisms more resistant to a range of pH survived while those more sensitive did not.

Gulick says the mass extinction event was probably not caused by just one mechanism, but rather a combination of environmental changes acting on different time scales, in different locations. For example, many large land animals might have been baked to death within hours or days of the impact as ejected material fell from the sky, heating the atmosphere and setting off firestorms. More gradual changes in climate and acidity might have had a larger impact in the oceans.

Wednesday, January 23, 2008

A Model For Flying Dinosaurs

A fundamental avian wing-stroke provides a new perspective on the evolution of flight. 2008. K. P. Dial et al. Nature, published online 23 January 2008.

How a young bird learns to fly—as shown here in this illustration of Chukar partridges—is dependent on its learning a certain wing angle, a new study says. Illustration courtesy Robert Petty.

Abstract: The evolution of avian flight remains one of biology's major controversies, with a long history of functional interpretations of fossil forms given as evidence for either an arboreal or cursorial origin of flight. Despite repeated emphasis on the 'wing-stroke' as a necessary avenue of investigation for addressing the evolution of flight, no empirical data exist on wing-stroke dynamics in an experimental evolutionary context.

Here we present the first comparison of wing-stroke kinematics of the primary locomotor modes (descending flight and incline flap-running) that lead to level-flapping flight in juvenile ground birds throughout development (Fig. 1).

The reader friendly version is at National Geographic News. Here’s there take home message:

How a young bird learns to fly—as shown here in this illustration of Chukar partridges—is dependent on its learning a certain wing angle, a new study says. Illustration courtesy Robert Petty.

Abstract: The evolution of avian flight remains one of biology's major controversies, with a long history of functional interpretations of fossil forms given as evidence for either an arboreal or cursorial origin of flight. Despite repeated emphasis on the 'wing-stroke' as a necessary avenue of investigation for addressing the evolution of flight, no empirical data exist on wing-stroke dynamics in an experimental evolutionary context.

Here we present the first comparison of wing-stroke kinematics of the primary locomotor modes (descending flight and incline flap-running) that lead to level-flapping flight in juvenile ground birds throughout development (Fig. 1).

The fundamental wing-stroke described herein is used days after hatching and during all ages and over multiple behaviours (that is, flap-running, descending and level flight) and is the foundation of our new ontogenetic-transitional wing hypothesis. At hatching, chicks can ascend inclines as steep as 60° by crawling on all four limbs. From day 8 through adulthood, birds use a consistently orientated stroke-plane angle over all substrate inclines during wing-assisted incline running (red arcs) as well as during descending and level flight (blue arcs). Estimated force orientations from this conserved wing-stroke are limited to a narrow wedge (see Fig. 3b).

We offer results that are contrary both to popular perception and inferences from other studies. Starting shortly after hatching and continuing through adulthood, ground birds use a wing-stroke confined to a narrow range of less than 20°, when referenced to gravity, that directs aerodynamic forces about 40° above horizontal, permitting a 180° range in the direction of travel. Based on our results, we put forth an ontogenetic-transitional wing hypothesis that posits that the incremental adaptive stages leading to the evolution of avian flight correspond behaviourally and morphologically to transitional stages observed in ontogenetic forms.CLICK TO ENLARGE

a, When wing-stroke plane angles are viewed side-by-side in both the vertebral and gravitational frames of reference, the wing-stroke is nearly invariant relative to gravity whereas the body axis re-orients among different modes of locomotion. Red lines represent the wing-tip trace in WAIR (flap-running) and blue lines represent the wing-tip trace in level flight. b, Wing-strokes are estimated to produce similar aerodynamic forces oriented about 40° above the horizon during WAIR, level flight and descending flight. Error bars are s.e.m. c, Representative traces of AOA through a wing-beat for an animal flap-running vertically (red) and in horizontal flight (blue) demonstrate the similarities of AOA among behaviours. The similarities are further clarified by examining wing cross-sections and mean global stroke-planes in the first, middle and last thirds of downstroke. Here, the orientation of the aerodynamic force (Faero) is estimated from the middle third.The reader friendly version is at National Geographic News. Here’s there take home message:

The way in which vulnerable young birds use their wings while transitioning into adult bodies could be a model for how their ancestors developed the ability to fly, Dial said.

"When you step back and look at the fossils they are finding, the long-legged dinosaurs with half a wing, they look very uncannily like today's birds that are going through the juvenile stage," he said.

How Old Is That Platypus In The Window?

The oldest platypus and its bearing on divergence timing of the platypus and echidna clades. 2008. T. Rowe et al. PNAS, published online before print January 23, 2008.

Platypuses and their closest evolutionary relatives, the four echidna species, were thought to have split from a common ancestor sometime in the past 17 million to 65 million years. But remains of what was believed to be a distant forebear of both the platypus and the echidna—the fossil species Teinolophos—actually belong to an early platypus, according to scientists who performed an x-ray analysis of a Teinolophos jawbone. The finding means the two animals must have separated sometime earlier than the age of the fossil—at least 112 million years ago.

Platypus bills are complex sensory organs loaded with electrical receptors. In murky waters the animals hunt by tracking the weak electrical fields generated by muscle activity in fish and other prey.

All mammals have some type of canal that conducts nerve fibers to the teeth, Rowe noted. But in the platypus, this canal is greatly enlarged to accommodate a massive network of fibers that carry sensory information from the bill. The claim that Teinolophos is a very ancient platypus rests largely on this feature.

But Matt Phillips, of the Australian National University in Canberra, said more evidence may be needed. The research "does not confirm that the platypuses and echidnas diverged more than 112 million years ago," Phillips said. Read his counter argument HERE.

This is another Open Access article so you should be able to download the PDF HERE.

CT scans of a fossil jawbone reveal a large jaw canal in a creature once thought to be a forbearer of the platypus and related species. Images: T. Rowe

From National Geographic News:Platypuses and their closest evolutionary relatives, the four echidna species, were thought to have split from a common ancestor sometime in the past 17 million to 65 million years. But remains of what was believed to be a distant forebear of both the platypus and the echidna—the fossil species Teinolophos—actually belong to an early platypus, according to scientists who performed an x-ray analysis of a Teinolophos jawbone. The finding means the two animals must have separated sometime earlier than the age of the fossil—at least 112 million years ago.

Platypus bills are complex sensory organs loaded with electrical receptors. In murky waters the animals hunt by tracking the weak electrical fields generated by muscle activity in fish and other prey.

All mammals have some type of canal that conducts nerve fibers to the teeth, Rowe noted. But in the platypus, this canal is greatly enlarged to accommodate a massive network of fibers that carry sensory information from the bill. The claim that Teinolophos is a very ancient platypus rests largely on this feature.

But Matt Phillips, of the Australian National University in Canberra, said more evidence may be needed. The research "does not confirm that the platypuses and echidnas diverged more than 112 million years ago," Phillips said. Read his counter argument HERE.

This is another Open Access article so you should be able to download the PDF HERE.

Discovery Day at the CMNH

Every MLK Day (a national holiday in the US), the Cleveland Museum of Natural History offers free admission to the public. Last Monday curators, staff and volunteers set up displays throughout the museum and talked to the public.

VP technician, David Chapman explains the action of Dunkleosteous jaws.

VP volunteer, Katie, talks about prehistoric sharks.

VP volunteer, Joe Klunder, and technician, Gary Jackson, talk up fossils.

Invertebrate Paleo curator, Joe Hannibal, does his thing.

The Paleobotany display.

Mineralogist, Dr. David Saja.

Physical Anthropology.

Anne from Phys. Anthro works on a fossil skull reconstruction.

Dr. Brian Redmond, one of our Archaeologists

Harold Edleman, one of our long-time volunteers (he proudly turns 97 this year) poses with our new Triceratops mount.

VP technician, David Chapman explains the action of Dunkleosteous jaws.

VP volunteer, Katie, talks about prehistoric sharks.

VP volunteer, Joe Klunder, and technician, Gary Jackson, talk up fossils.

Invertebrate Paleo curator, Joe Hannibal, does his thing.

The Paleobotany display.

Mineralogist, Dr. David Saja.

Physical Anthropology.

Anne from Phys. Anthro works on a fossil skull reconstruction.

Dr. Brian Redmond, one of our Archaeologists

Harold Edleman, one of our long-time volunteers (he proudly turns 97 this year) poses with our new Triceratops mount.

Mega-Tsunami and Extraordinary Claims

Impacts, mega-tsunami, and other extraordinary claims. 2008. Nicholas Pinter and Scott E. Ishman. GSA Today 18

Pinter and Ishman have a nice, short, open-access article in the latest GSA Today about the claims for Holocene-age ocean impacts and associated “mega-tsunami,” and a catastrophic impact event suggested at 12.9 ka.

“The 12.9-ka impact theory also runs roughshod over a wide range of other evidence. The claim that American megafauna disappeared precisely at 12.9 ka is contrary to broad evidence that these extinctions were diachronous in space, across genera, and dependent on local geographical conditions (Fiedel, 2008). Similarly, the “black mat” horizons characterized by the Firestone group as a single hemisphere-wide impact-induced wildfire are elsewhere reported as multiple horizons of wetland deposits that span the latest Pleistocene-Holocene (Quade et al., 1998)”.

Pinter and Ishman have a nice, short, open-access article in the latest GSA Today about the claims for Holocene-age ocean impacts and associated “mega-tsunami,” and a catastrophic impact event suggested at 12.9 ka.

“The 12.9-ka impact theory also runs roughshod over a wide range of other evidence. The claim that American megafauna disappeared precisely at 12.9 ka is contrary to broad evidence that these extinctions were diachronous in space, across genera, and dependent on local geographical conditions (Fiedel, 2008). Similarly, the “black mat” horizons characterized by the Firestone group as a single hemisphere-wide impact-induced wildfire are elsewhere reported as multiple horizons of wetland deposits that span the latest Pleistocene-Holocene (Quade et al., 1998)”.

Tuesday, January 22, 2008

Rise of the Pollinators

Early steps of angiosperm–pollinator coevolution. 2008. Shusheng Hue et al., Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. 105: 240-245.

From the press release:

Researchers have pinpointed a 96-million-year-old timeframe as the turning point in the evolution of basal angiosperm groups when they were predominantly insect-pollinated. The study also is the first to describe the biological structure of pollen clumping in the early Late Cretaceous, which holds clues about the types of pollinators with which they were coevolving.

Today, flowers specialized for insect pollination disperse clumps of five to 100 pollen grains. Clumped grains are comparatively larger and have more surface relief than wind- or water-dispersed pollen, which tend to be single, smaller and smoother.

The study provides strong evidence for the widely accepted hypothesis that insects drove the massive adaptive radiation of early flowering plants when they rapidly diversified and expanded to exploit new terrestrial niches. Land plants first appear in the fossil record about 425 million years ago, but flowering plants didn't appear until about 125 million years ago in the Early Cretaceous period.

The nine species of fossil pollen clumps, combined with known structural changes occurring in flowering plants at this time, led the researchers to suggest that insect pollination was well established by the early Late Cretaceous -- only a few million years before the explosion in diversity and distribution of flowering plant families. Known structural changes include early prototypes of stamen and anther, plant organs which lift pollen up and away from the plant, positioning the plants' genetic material to be passed off to visiting insects.

From the press release:

Researchers have pinpointed a 96-million-year-old timeframe as the turning point in the evolution of basal angiosperm groups when they were predominantly insect-pollinated. The study also is the first to describe the biological structure of pollen clumping in the early Late Cretaceous, which holds clues about the types of pollinators with which they were coevolving.

Today, flowers specialized for insect pollination disperse clumps of five to 100 pollen grains. Clumped grains are comparatively larger and have more surface relief than wind- or water-dispersed pollen, which tend to be single, smaller and smoother.

The study provides strong evidence for the widely accepted hypothesis that insects drove the massive adaptive radiation of early flowering plants when they rapidly diversified and expanded to exploit new terrestrial niches. Land plants first appear in the fossil record about 425 million years ago, but flowering plants didn't appear until about 125 million years ago in the Early Cretaceous period.

The nine species of fossil pollen clumps, combined with known structural changes occurring in flowering plants at this time, led the researchers to suggest that insect pollination was well established by the early Late Cretaceous -- only a few million years before the explosion in diversity and distribution of flowering plant families. Known structural changes include early prototypes of stamen and anther, plant organs which lift pollen up and away from the plant, positioning the plants' genetic material to be passed off to visiting insects.

Monday, January 21, 2008

Linus Knows Everything

Saturday, January 19, 2008

Psittacosaurus Flesh Wound

A unique cross section through the skin of the dinosaur Psittacosaurus from China showing a complex fibre architecture. 2008. Theagarten Lingham-Solia. Proc. Royal Society B, published on-line, Tuesday, January 08, 2008

Illustration courtesy Theagarten Lingham-Soliar

The fossil is of a 130-million-year-old Psittacosaurus died after suffering a wound from a predator—or was perhaps bitten by a scavenger after it died—exposing the inner skin structure, which was preserved for millions of years. A recent study of the fossil identified what appeared to be tooth marks in the wound.

Lingham-Soliar has identified what he says is fossilized surface skin as well as a cross-section of the thick layer below the surface, called the dermis, around the animal's lower left side.

The animal's skin was at least 0.8 inch (2 centimeters) thick, with some 40 layers of a fibrous protein called collagen, making it ideal for defense against predators.

The research also suggests that some dinosaurs had thick, scaly skin like that of modern-day reptiles, refuting the theory that dinos had primitive feathers. [really?, ed.]

Illustration courtesy Theagarten Lingham-Soliar

The fossil of a dinosaur with a flesh wound has been discovered in northeastern China, offering the most complete view to date of dinosaur skin, a scientist says.From National Geographic News:

The fossil is of a 130-million-year-old Psittacosaurus died after suffering a wound from a predator—or was perhaps bitten by a scavenger after it died—exposing the inner skin structure, which was preserved for millions of years. A recent study of the fossil identified what appeared to be tooth marks in the wound.

Lingham-Soliar has identified what he says is fossilized surface skin as well as a cross-section of the thick layer below the surface, called the dermis, around the animal's lower left side.

The animal's skin was at least 0.8 inch (2 centimeters) thick, with some 40 layers of a fibrous protein called collagen, making it ideal for defense against predators.

The research also suggests that some dinosaurs had thick, scaly skin like that of modern-day reptiles, refuting the theory that dinos had primitive feathers. [really?, ed.]

Recovery From The Permian Extinction

Recovery from the most profound mass extinction of all time. 2007. Sarda Sahney andMichael J. Benton. Proc. Royal Acad. B., on-line publication, Tuesday, January 15, 2008.

Abstract: The end-Permian mass extinction, 251 million years ago, was the most devastating ecological event of all time, and it was exacerbated by two earlier events at the beginning and end of the Guadalupian, 270 and 260Myr ago. Ecosystems were destroyed worldwide, communities were restructured and organisms were left struggling to recover. Disaster taxa, such as Lystrosaurus, insinuated themselves into almost every corner of the sparsely populated landscape in the earliest Triassic, and a quick taxonomic recovery apparently occurred on a global scale.

However, close study of ecosystem evolution shows that true ecological recovery was slower. After the end-Guadalupian event, faunas began rebuilding complex trophic structures and refilling guilds, but were hit again by the end-Permian event. Taxonomic diversity at the alpha (community) level did not recover to pre-extinction levels; it reached only a low plateau after each pulse and continued low into the Late Triassic. Our data showed that though there was an initial rise in cosmopolitanism after the extinction pulses, large drops subsequently occurred and, counter-intuitively, a surprisingly low level of cosmopolitanism was sustained through the Early and Middle Triassic.

The PDF

Abstract: The end-Permian mass extinction, 251 million years ago, was the most devastating ecological event of all time, and it was exacerbated by two earlier events at the beginning and end of the Guadalupian, 270 and 260Myr ago. Ecosystems were destroyed worldwide, communities were restructured and organisms were left struggling to recover. Disaster taxa, such as Lystrosaurus, insinuated themselves into almost every corner of the sparsely populated landscape in the earliest Triassic, and a quick taxonomic recovery apparently occurred on a global scale.

However, close study of ecosystem evolution shows that true ecological recovery was slower. After the end-Guadalupian event, faunas began rebuilding complex trophic structures and refilling guilds, but were hit again by the end-Permian event. Taxonomic diversity at the alpha (community) level did not recover to pre-extinction levels; it reached only a low plateau after each pulse and continued low into the Late Triassic. Our data showed that though there was an initial rise in cosmopolitanism after the extinction pulses, large drops subsequently occurred and, counter-intuitively, a surprisingly low level of cosmopolitanism was sustained through the Early and Middle Triassic.

The PDF

Friday, January 18, 2008

Largest Fossil Rodent

The Largest Fossil Rodent. 2008. Andrés Rinderknecht and R. Ernesto Blanco. Proc. of the Royal Acad. B., on-line pub. Tuesday, January 15, 2008.

Abstract: The discovery of an exceptionally well-preserved skull permits the description of the new South American fossil species of the rodent, Josephoartigasia monesi sp. nov. (family: Dinomyidae; Rodentia: Hystricognathi: Caviomorpha). This species with estimated body mass of nearly 1000kg is the largest yet recorded. The skull sheds new light on the anatomy of the extinct giant rodents of the Dinomyidae, which are known mostly from isolated teeth and incomplete mandible remains. The fossil derives from San José Formation, Uruguay, usually assigned to the Pliocene–Pleistocene (4–2Myr ago), and the proposed palaeoenvironment where this rodent lived was characterized as an estuarine or deltaic system with forest communities.

Abstract: The discovery of an exceptionally well-preserved skull permits the description of the new South American fossil species of the rodent, Josephoartigasia monesi sp. nov. (family: Dinomyidae; Rodentia: Hystricognathi: Caviomorpha). This species with estimated body mass of nearly 1000kg is the largest yet recorded. The skull sheds new light on the anatomy of the extinct giant rodents of the Dinomyidae, which are known mostly from isolated teeth and incomplete mandible remains. The fossil derives from San José Formation, Uruguay, usually assigned to the Pliocene–Pleistocene (4–2Myr ago), and the proposed palaeoenvironment where this rodent lived was characterized as an estuarine or deltaic system with forest communities.

More Photos From Argentina

Lots to post on but I'm busy. So, here are more photos from Eric's trip to Argentina:

The dicraeosaurid sauropod Amargasaurus, with its hyper-elongate neural spines. More bizarre and elegant in person. Museo National de Siencias Naturales, Buenos Aires.

The abelisaurid theropod Carnotaurus inspires its share of vivid sculptures, including this in Buenos Aires and Stephen Czerkas' at the L.A. County Museum.

Darned good Tyrannosaurus rex by J.A. Gonzales, in the North American dinosaurs exhibit at el Museo National de Siencias Naturales, Buenos Aires.

Well-preserved distal tail of the ankylosaur Euoplocephalus tutus, from Alberta, Canada.

Most of the largest sauropod dinosaurs lived in Argentina about 100 million years ago. Their likely fodder, araucarian conifers, are still here

The dicraeosaurid sauropod Amargasaurus, with its hyper-elongate neural spines. More bizarre and elegant in person. Museo National de Siencias Naturales, Buenos Aires.

The abelisaurid theropod Carnotaurus inspires its share of vivid sculptures, including this in Buenos Aires and Stephen Czerkas' at the L.A. County Museum.

Darned good Tyrannosaurus rex by J.A. Gonzales, in the North American dinosaurs exhibit at el Museo National de Siencias Naturales, Buenos Aires.

Well-preserved distal tail of the ankylosaur Euoplocephalus tutus, from Alberta, Canada.

Most of the largest sauropod dinosaurs lived in Argentina about 100 million years ago. Their likely fodder, araucarian conifers, are still here

Thursday, January 17, 2008

Your Inner Fish

From the latest issue of Nature comes this review of Neil Shubin’s new book by Carl Zimmer.

“Six hundred years ago, anatomists were rock stars. Their lessons filled open-air amphitheatres, where the curious public rubbed shoulders with medical students. While a surgeon sliced open a cadaver, the anatomist, seated above on a lofty chair, deciphered the exposed mysteries of the bones, muscles and organs.

Modern anatomists have retreated from the stage to windowless medical-school labs. They have ceded their public role to geneticists unveiling secrets encrypted in our DNA. Yet anatomists may be poised for a comeback, judging from Your Inner Fish. Neil Shubin, a biologist and palaeontologist at the University of Chicago, Illinois, delves into human gristle, interpreting the scars of billions of years of evolution that we carry inside our bodies.

Your Inner Fish combines Shubin's and others' discoveries to present a twenty-first-century anatomy lesson. The simple, passionate writing may turn more than a few high-school students into aspiring biologists. And it covers a lot of ground. Shubin inspects our eyeballs, noses and hands to demonstrate how much we have in common with other animals. He notes how networks of genes for simple traits can expand and diversify until they build new complex structures such as heads. Also, that hangovers explain how our ears evolved from sensory cells on the surface of fish. He investigates the hiccup, the result of a tortuous nervous system.”

T. DAESCHLER, ACADEMY OF NATURAL SCIENCES OF PHILADELPHIA/J. WEINSTEIN, FIELD MUSEUM. Author Neil Shubin (above) discovered the transitional fossil Tiktaalik roseae (below).

Your Inner Fish: A Journey into the 3.5-Billion-Year History of the Human Body by Neil Shubin. Allen Lane/Pantheon: 2008. 240 pp.“Six hundred years ago, anatomists were rock stars. Their lessons filled open-air amphitheatres, where the curious public rubbed shoulders with medical students. While a surgeon sliced open a cadaver, the anatomist, seated above on a lofty chair, deciphered the exposed mysteries of the bones, muscles and organs.

Modern anatomists have retreated from the stage to windowless medical-school labs. They have ceded their public role to geneticists unveiling secrets encrypted in our DNA. Yet anatomists may be poised for a comeback, judging from Your Inner Fish. Neil Shubin, a biologist and palaeontologist at the University of Chicago, Illinois, delves into human gristle, interpreting the scars of billions of years of evolution that we carry inside our bodies.

Your Inner Fish combines Shubin's and others' discoveries to present a twenty-first-century anatomy lesson. The simple, passionate writing may turn more than a few high-school students into aspiring biologists. And it covers a lot of ground. Shubin inspects our eyeballs, noses and hands to demonstrate how much we have in common with other animals. He notes how networks of genes for simple traits can expand and diversify until they build new complex structures such as heads. Also, that hangovers explain how our ears evolved from sensory cells on the surface of fish. He investigates the hiccup, the result of a tortuous nervous system.”

Born This Day: August Weismann

Jan. 17, 1834 – Nov. 5, 1914

From Today In Science History:

August (Friedrich Leopold) Weismann was a German biologist and one of the founders of the science of genetics. He is best known for his opposition to the doctrine of the inheritance of acquired traits and for his "germ plasm" theory, the forerunner of DNA theory. Weismann conceived the idea, arising out of his early observations on the Hydrozoa, that the germ cells of animals contain "something essential for the species, something which must be carefully preserved and passed on from one generation to another." Weismann envisioned the hereditary substances from the two parents become mixed together in the fertilized egg and a form of nuclear division in which each daughter nucleus receives only half the original ancestral germ plasms.

was a German biologist and one of the founders of the science of genetics. He is best known for his opposition to the doctrine of the inheritance of acquired traits and for his "germ plasm" theory, the forerunner of DNA theory. Weismann conceived the idea, arising out of his early observations on the Hydrozoa, that the germ cells of animals contain "something essential for the species, something which must be carefully preserved and passed on from one generation to another." Weismann envisioned the hereditary substances from the two parents become mixed together in the fertilized egg and a form of nuclear division in which each daughter nucleus receives only half the original ancestral germ plasms.

More info from Science World. image

From Today In Science History:

August (Friedrich Leopold) Weismann

was a German biologist and one of the founders of the science of genetics. He is best known for his opposition to the doctrine of the inheritance of acquired traits and for his "germ plasm" theory, the forerunner of DNA theory. Weismann conceived the idea, arising out of his early observations on the Hydrozoa, that the germ cells of animals contain "something essential for the species, something which must be carefully preserved and passed on from one generation to another." Weismann envisioned the hereditary substances from the two parents become mixed together in the fertilized egg and a form of nuclear division in which each daughter nucleus receives only half the original ancestral germ plasms.

was a German biologist and one of the founders of the science of genetics. He is best known for his opposition to the doctrine of the inheritance of acquired traits and for his "germ plasm" theory, the forerunner of DNA theory. Weismann conceived the idea, arising out of his early observations on the Hydrozoa, that the germ cells of animals contain "something essential for the species, something which must be carefully preserved and passed on from one generation to another." Weismann envisioned the hereditary substances from the two parents become mixed together in the fertilized egg and a form of nuclear division in which each daughter nucleus receives only half the original ancestral germ plasms.More info from Science World. image

Wednesday, January 16, 2008

More Dino Teen Pregnancies

Sexual maturity in growing dinosaurs does not fit reptilian growth models. 2007. Andrew H. Lee and Sarah Werning. PNAS 105: 582-587.

Cross-sections through the fossilized tibia of a 120 million-year-old female Tenontosaurus, showing growth rings and medullary bone laid done in the marrow cavity just prior to egg laying. This individual died at the age of eight, shortly before she would have laid her eggs. Credit:Sarah Werning/UC Berkeley & Andrew Lee/Ohio U.

Researchers have found medullary bone – the same tissue that allows birds to develop eggshells – in two new dinosaur specimens: the meat-eater Allosaurus and the plant-eater Tenontosaurus. It’s previuosly been found in Tyrannosaurus rex.

The discovery allowed researchers to pinpoint the age of these pregnant dinosaurs, which were 8, 10 and 18. That suggests that the creatures reached sexual maturity earlier than previously thought, according to the scientists.

The new study suggests another explanation: Dinosaurs grew fast but only lived three to four years in adulthood. Offspring were probably precocious, like calves or foals, Lee said.

“We were lucky to find these female fossils,” Werning said. “Medullary bone is only around for three to four weeks in females who are reproductively mature, so you’d have to cut up a lot of dinosaur bones to have a good chance of finding this.”

The research also offers more evidence that dinosaurs were less like reptiles and more like birds. Though dinosaurs had offspring before adulthood, their early sexual maturity was more a function of their tremendous size than any anatomical similarity to crocodiles.

The discovery also sheds new light on the evolution of birds. The presence of medullary tissue in these dinosaurs, which lived as long as 200 million years ago, shows that the reproductive strategies of modern birds have ancient origins.

Cross-sections through the fossilized tibia of a 120 million-year-old female Tenontosaurus, showing growth rings and medullary bone laid done in the marrow cavity just prior to egg laying. This individual died at the age of eight, shortly before she would have laid her eggs. Credit:Sarah Werning/UC Berkeley & Andrew Lee/Ohio U.

Dinosaurs had pregnancies as early as age 8, far before they reached their maximum adult size, a new study finds.From the press release:

Researchers have found medullary bone – the same tissue that allows birds to develop eggshells – in two new dinosaur specimens: the meat-eater Allosaurus and the plant-eater Tenontosaurus. It’s previuosly been found in Tyrannosaurus rex.

The discovery allowed researchers to pinpoint the age of these pregnant dinosaurs, which were 8, 10 and 18. That suggests that the creatures reached sexual maturity earlier than previously thought, according to the scientists.

The new study suggests another explanation: Dinosaurs grew fast but only lived three to four years in adulthood. Offspring were probably precocious, like calves or foals, Lee said.

“We were lucky to find these female fossils,” Werning said. “Medullary bone is only around for three to four weeks in females who are reproductively mature, so you’d have to cut up a lot of dinosaur bones to have a good chance of finding this.”

The research also offers more evidence that dinosaurs were less like reptiles and more like birds. Though dinosaurs had offspring before adulthood, their early sexual maturity was more a function of their tremendous size than any anatomical similarity to crocodiles.

The discovery also sheds new light on the evolution of birds. The presence of medullary tissue in these dinosaurs, which lived as long as 200 million years ago, shows that the reproductive strategies of modern birds have ancient origins.

The Next Generation of Mongolian Dinosaur Palaeontologists

Baasanjav Ugtbayar, left, and Minjin Chuluun record data from a Mongolian field site. Chuluun is a paleontology and geology professor at Mongolian University Science and Technology. (Photo courtesy of Bolortsetseg Minjin).

Jack Horner has flown to Mongolia the past three summers to search for dinosaur bones. Now three members of his field crew have joined him at Montana State University to start developing a new generation of Mongolian paleontologists.

"I had this dream that I wanted Mongolian paleontology to be developed better," said Bolortsetseg Minjin, a postdoctoral researcher. "I wanted Mongolian paleontologists to work on Mongolian species."

Mongolia already has paleontologists. Her father is one of them, Bolortsetseg said. But most Mongolian paleontologists are older than 50, and many were trained in Russia during the Communist years, she said. Now that Mongolia is open to the West, she'd like to see more young people study paleontology, especially vertebrate paleontology, and learn the latest technology and research methods from western scientists. She wants them to work in state-of-the-art laboratories in their own country.

"In terms of my generation, there are not many people, basically just me," Bolortsetseg said. "That's kind of scary."

She said she considers the Museum of the Rockies to be the top training facility for paleontologists in the United States, which is why she asked Horner if she could work with him. The two met four years ago during Horner's first field season in Mongolia. She also asked if Baasanjav Ugtbayar and Badamkhatan Zorigt could join them.

Horner agreed, and the three are now the only Mongolians studying paleontology in the United States, Bolortsetseg said. The Mongolian research and student projects are being funded by private donations. After the Mongolians finish at MSU, they plan to return home with the ability to find, excavate and study Mongolia's dinosaurs for themselves. Horner supports the idea.

"It's not about me," Horner said. "It's about science. It's about getting data. Obviously, the better the data, the better the questions you can ask. You want people that have been trained well to be out there.

Horner's teams of paleontologists found 180 psittacosaurus skeletons over three field seasons in Mongolia. They excavated as many as 80 in one week. The fossils remain in Mongolia, but Bolortsetseg said she will fly there this spring to retrieve some of the longer bones to prepare and study at the Museum of the Rockies. She especially wants to spend time in the museum's histology lab, learning new methods of studying the dinosaur bones.

Baasanjav and Badamkhatan will work at the museum and study English at the Ace Language Institute in Bozeman this spring. In the fall, Baasanjav will start working on her master's degree. She expects it will take her about two years to complete. Badamkhatan will continue working on his doctorate.

Bolortsetseg received her doctorate in paleontology last summer from the City University of New York. Last year, she established the "Institute for the Study of Mongolian Dinosaurs," a research and educational institution in Mongolia. After Bassanjav and Badamkhatan earn their graduate degrees, they will become researchers at this non-profit, non-government institute.

There is actually a lot of info in this press release if you read between the lines. Hearty congratulations to Jack and others in NA for supporting the new generation of Mongolian vertebrate palaeontologists

Monday, January 14, 2008

Baryonyx (with a fish)

From the press release:

The unusual skull of Baryonyx is very elongate, with a curved or sinuous jaw margin as seen in large crocodiles and alligators. It also had stout conical teeth, rather than the blade-like serrated ones in meat-eating dinosaurs, and a striking bulbous jaw tip (or ‘nose’) that bore a rosette of teeth, more commonly seen today in slender-jawed fish eating crocodilians such as the Indian fish-eating gharial. Baryonyx walkeri is an early Cretaceous dinosaur, around 125 million years old, and belongs to a family called spinosaurs.

Baryonyx snout bone is transparent brown; the teeth (yellow) had extremely deep roots; Baryonyx independently evolved a bony palate (the pink structure), also seen in crocodilians. Credit: Emily Rayfield

Rayfield used computer modelling techniques to show that while Baryonyx was eating, its skull bent and stretched in the same way as the skull of the Indian fish-eating gharial – a crocodile with long, narrow jaws. The results wer published in the latest JVP.

Dr Rayfield said: “On excavation, partially digested fish scales and teeth, and a dinosaur bone were found in the stomach region of the animal, demonstrating that at least some of the time this dinosaur ate fish. Moreover, it had a very unusual skull that looked part-dinosaur and part-crocodile, so we wanted to establish which it was more similar to, structurally and functionally – a dinosaur or a crocodile.

The results showed that the eating behaviour of Baryonyx was markedly different from that of a typical meat-eating theropod dinosaur or an alligator, and most similar to the fish-eating gharial. Since the bulk of the gharial diet consists of fish, Rayfield’s study suggests that this was also the case for Baryonyx back in the Cretaceous.

The unusual skull of Baryonyx is very elongate, with a curved or sinuous jaw margin as seen in large crocodiles and alligators. It also had stout conical teeth, rather than the blade-like serrated ones in meat-eating dinosaurs, and a striking bulbous jaw tip (or ‘nose’) that bore a rosette of teeth, more commonly seen today in slender-jawed fish eating crocodilians such as the Indian fish-eating gharial. Baryonyx walkeri is an early Cretaceous dinosaur, around 125 million years old, and belongs to a family called spinosaurs.

Baryonyx snout bone is transparent brown; the teeth (yellow) had extremely deep roots; Baryonyx independently evolved a bony palate (the pink structure), also seen in crocodilians. Credit: Emily Rayfield

Rayfield used computer modelling techniques to show that while Baryonyx was eating, its skull bent and stretched in the same way as the skull of the Indian fish-eating gharial – a crocodile with long, narrow jaws. The results wer published in the latest JVP.

Dr Rayfield said: “On excavation, partially digested fish scales and teeth, and a dinosaur bone were found in the stomach region of the animal, demonstrating that at least some of the time this dinosaur ate fish. Moreover, it had a very unusual skull that looked part-dinosaur and part-crocodile, so we wanted to establish which it was more similar to, structurally and functionally – a dinosaur or a crocodile.

The results showed that the eating behaviour of Baryonyx was markedly different from that of a typical meat-eating theropod dinosaur or an alligator, and most similar to the fish-eating gharial. Since the bulk of the gharial diet consists of fish, Rayfield’s study suggests that this was also the case for Baryonyx back in the Cretaceous.

Saturday, January 12, 2008

Dinosaurs These Days

The ever busy Pete Von Sholly has produced a fun line off coffee mugs with the theme of "Dinosaurs These Days". Some of the images are reproduced here and you can order them up from Cafe Express.

And for those of you who like to mix your politics with the old Universal Monsters, check out Pete's new trading card series. Collect them all!

And for those of you who like to mix your politics with the old Universal Monsters, check out Pete's new trading card series. Collect them all!