Those are Triceratops? Quite a wacky combination of dinos.

The bear that left a 3-foot-long claw mark in an Ice Age clay bank was the largest bear species ever to walk the Earth, about 6 feet tall at the shoulder and capable of moving its 1,800 pounds up to 45 mph in a snarling dash for prey.

From the Cleveland Plain Dealer:

From the Cleveland Plain Dealer:A trail of 13 fossilized footprints running through a valley in a desert in northern Mexico could be among the oldest in the Americas, Mexican archeologists said.

The famous fossil of Lucy is scheduled to tour the United States, but one place it won't be on display is the Smithsonian's National Museum of Natural History.From Yahoo! News:

Ethiopian officials had listed Washington as a stop on Lucy's tour, though they didn't specify where in Washington the skeleton would go. The tour arrangements are being made by the Houston Museum of Natural Science and not all locations have been finalized.

Ethiopian officials had listed Washington as a stop on Lucy's tour, though they didn't specify where in Washington the skeleton would go. The tour arrangements are being made by the Houston Museum of Natural Science and not all locations have been finalized.

Artist's rendering of a new species of phorusrhacid ("terror bird"). The fossil skull of the new specimen—seen in the bottom photo alongside a modern California condor--represents the largest bird skull ever found. Skull photos by S. Bertelli; illo by S. Abramowicz.From National Geographic News:

Modern lampreys, such as the fish pictured above, haven't changed much from their ancient ancestors, according to a new study of a 360-million-year-old fossil. Photo USFWS.Abstract: Lampreys are the most scientifically accessible of the remaining jawless vertebrates, but their evolutionary history is obscure. In contrast to the rich fossil record of armoured jawless fishes, all of which date from the Devonian period and earlier, only two Palaeozoic lampreys have been recorded, both from the Carboniferous period. In addition to these, the recent report of an exquisitely preserved Lower Cretaceous example demonstrates that anatomically modern lampreys were present by the late Mesozoic era.

which is established easily because many of the key specializations of modern forms are already in place. These specializations include the first evidence of a large oral disc, the first direct evidence of circumoral teeth and a well preserved branchial basket.

which is established easily because many of the key specializations of modern forms are already in place. These specializations include the first evidence of a large oral disc, the first direct evidence of circumoral teeth and a well preserved branchial basket. Dr. Eric Snively was recently in Warsaw on a research trip and filed this report for the Palaeoblog. All the photos and text are by Eric. Enjoy!North American palaeontologists are rarely able to visit the Institute of Paleobiology in Warsaw and associated exhibits at the Museum of Evolution, which harbor specimens collected during the Polish-Mongolian expeditions in the 1960s and 1970s. The expeditions are familiar to most of us through scientific and secondary descriptions of collected dinosaurs, and were led by the great Zofia Kielan-Jawoworska and detailed in her book Hunting for Dinosaurs. Despite a creationist-tinged contemporary government, Poland has a grand and still extraordinarily vital tradition in geology and palaeontology. On a recent visit to photograph Cretaceous lizards, I took general photographs that may be of interest to Palaeoblog readers. Thanks to Madgelena Borsuk-Bialynika and Karol Sabath for scientific guidance and hospitality.

Gogonasus, a fish that swam on an ancient barrier reef in Australia 380 million years ago had fins and nostrils remarkably similar to the limbs and ears of the first four-limbed creatures to walk on land, according to a new study.From National Geographic News:

The bones of an extinct dwarf species of buffalo were recently unearthed on the Philippine island of Cebu.

Researchers have discovered an isolated community of bacteria nearly two miles underground that derives all of its energy from the decay of radioactive rocks rather than from sunlight.The self-sustaining bacterial community, which thrives in nutrient-rich groundwater found near a South African gold mine, has been isolated from the Earth's surface for several million years. It represents the first group of microbes known to depend exclusively on geologically produced hydrogen and sulfur compounds for nourishment. The extreme conditions under which the bacteria live bear a resemblance to those of early Earth, potentially offering insights into the nature of organisms that lived long before our planet had an oxygen atmosphere.

Yes, yes, GSA and SVP meetings are all well and good but I REALLY wish that I had been at the 2nd Annual Zombie Walk in Calgary. Grr…!Thanks to Sukie and The 7 Deadly Sinners!

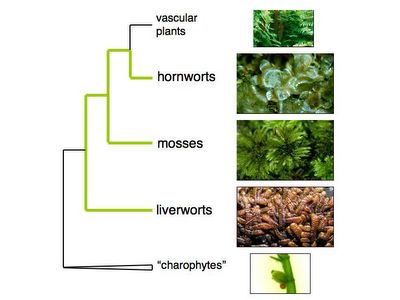

when charophyte algae first came onto land, and an obscure group called hornworts, often found in abandoned corn fields, represents the progenitors of the vascular plants.

when charophyte algae first came onto land, and an obscure group called hornworts, often found in abandoned corn fields, represents the progenitors of the vascular plants.A team of scientists has completed a study that explains why the tropics are so much richer in biodiversity than higher latitudes.From the U of Chicago press release: